MacKenzie Scott has been donating to HBCUs and Black educational organizations since at least 2020. In 2025 alone, we had seventy million dollars to the United Negro College Fund, $63 million to Prairie View A&M University, $50 million to Bowie State University, $19 million to Philander Smith University, and another $19 million to Dillard. The Scott donations have appeared in waves. All of them are unrestricted, and many are of unprecedented size for their recipient institution—both novelties in the philanthropy world.

She’s also donated to non-Black institutions, including tribal colleges (ex. Little Priest Tribal College), community colleges (ex. Northern Oklahoma College) and various non-educational organizations. Just a few days ago[EE1] , it was reported that Scott gave a $45 million gift to The Trevor Project, a non-profit LGBTQ+ suicide prevention organization that lost significant funding due to federal budget cuts.

My knee-jerk reaction to all this money was skepticism. Though she’s an award-winning novelist and a mentee of Toni Morrison, Scott is probably best known today as the former wife of Amazon co-founder Jeff Bezos. But skepticism quickly gave way to guilt. I went to college for almost nothing because I attended a school enriched through slavery and Indigenous dispossession. Who am I to self-deputize as the morality police?

As I’ve reflected on my feelings about these donations, I’ve come to three distinct conclusions. When summed together, they create something of a framework for how I metabolize these acts of big-figure philanthropy.

Head Up, Eyes Open

Philanthropy and reputation laundering go hand in hand. Writing with the best interests of the philanthropist in mind, IMD notes that philanthropic activity “can play a key role in reputation management.” More critically, an op-ed in Teen Vogue described “Big Philanthropy” as a “scam that makes the rich look better.”

Some such scammy qualities: Big Philanthropy has done nothing to diminish billionaires’ accelerating accumulation of wealth. In fact, charitable giving helps to maintain this wealth through the conferral of tax benefits. And though we’d like to imagine philanthropy as a Robin Hood-ian task of taking money from the rich and giving it to the poor, “a lot of elite philanthropy is about elite causes”—helping to further reproduce the inequalities that allegedly demand the existence of philanthropy in the first place.

The logic of philanthropy also negatively impacts beneficiaries. Most non-profits exist within what Inc. describes as a “‘dual customer’ dynamic.” Even though the non-profit has an altruistic obligation to their target population, it may prioritize the philanthropist’s desires over the community’s needs to keep the lights on.

Or philanthropists may simply favor their personal interests, passing over would-be beneficiaries entirely—like when hotelier Leona Helmsley left a $5 billion trust to be used for the welfare of dogs, having previously crossed out the part of her private mission statement that specified that the trust be used in helping poor people.

The Content of Their Character

Even knowing that philanthropy is a bit of a grift, I do think that an effective left must consider the entire lifespan of philanthropic dollars. As long as we live in an enclosed world, we’ll need to hold this money’s deeply unethical past and potentially productive future simultaneously.

This is not to make myself into a PR agent for Scott, nor to encourage us to discard core beliefs. But we are not in The Revolution; we’re actually living in what some scholars and intellectuals are calling a uniquely fascistic time. With that knowledge in mind, I think donating money to educational institutions—and not only to the big names that folks are most likely to know—sounds like one of the better choices one could make.

For context, here’s a non-exhaustive list of other ways that billionaires have chosen to spend their money: investing in “e-carceration” technologies, sending a motley crew of girl bosses to the edge of the atmosphere, bidding on art for private collections, buying a drive-thru safari, buying land in Hawaiʻi, buying Twitter, buying the Washington Post (so that the newspaper can produce pieces that align with your financial interests), and of course, giving it to the dogs.

I’ll also say that I don’t propose this thought experiment for its own sake—I believe that the critical thinking skills required to assess these donations in the context of who they’ll help and how will serve us in other ways. Here begins my brief retrospective on the 2024 Presidential Election.

For those of us who are politically left-of-center, the question of the Election was about whether to acknowledge Vice President Kamala Harris’ flaws as a candidate or to simply chant “She’s Not Trump!” as some sort of secular mantra. We’re used to this song and dance. Every four years, we cast our ballots for either (a) a walk or (b) a run towards climate catastrophe, for (a) violence in our backyards or (b) violence off in some unseen elsewhere. But this time around, the implications of accepting the lesser evil were more acutely felt. The Instagrammed genocide in Gaza shattered the false dichotomy, illustrating that violence here is necessarily violence there, and vice versa.

Some folks attempted to hold anti-Trump and anti-genocide positions at the same time; others prioritized the former at the latter’s expense. To that end, they did not implicate Harris as part of an administration that sent thousands of bombs and billions of dollars to Israel, which has, in turn, sliced Gaza’s life expectancy in half. And any critique of Harris, no matter how well-founded, was handwaved away as racism, misogyny, or a little bit of both (with Harris' Asianness often erased from the conversation altogether).

Had Harris been less insulated from good-faith criticism—had her partisans been more tolerant of critiques rooted in the things she actually did or didn’t do—perhaps her campaign positions would have evolved. Maybe she could have, if not inspired, then at least appeased the left-most contingent of the big Blue tent. I’m not so hubristic as to say that she definitely would have won in such a case, but the wisdom of hindsight shows that the strategy to place identity politics over material analysis was a losing one.

The Aforementioned Material Analysis

I’ve painted the practice of philanthropy with a large brush, and probably hypocritically, insisted that we evaluate each case of philanthropy based on its own merit. In an effort to reconcile the two takes, let’s turn back to MacKenzie Scott.

Donating money to colleges sounds good, but have her donations done good?

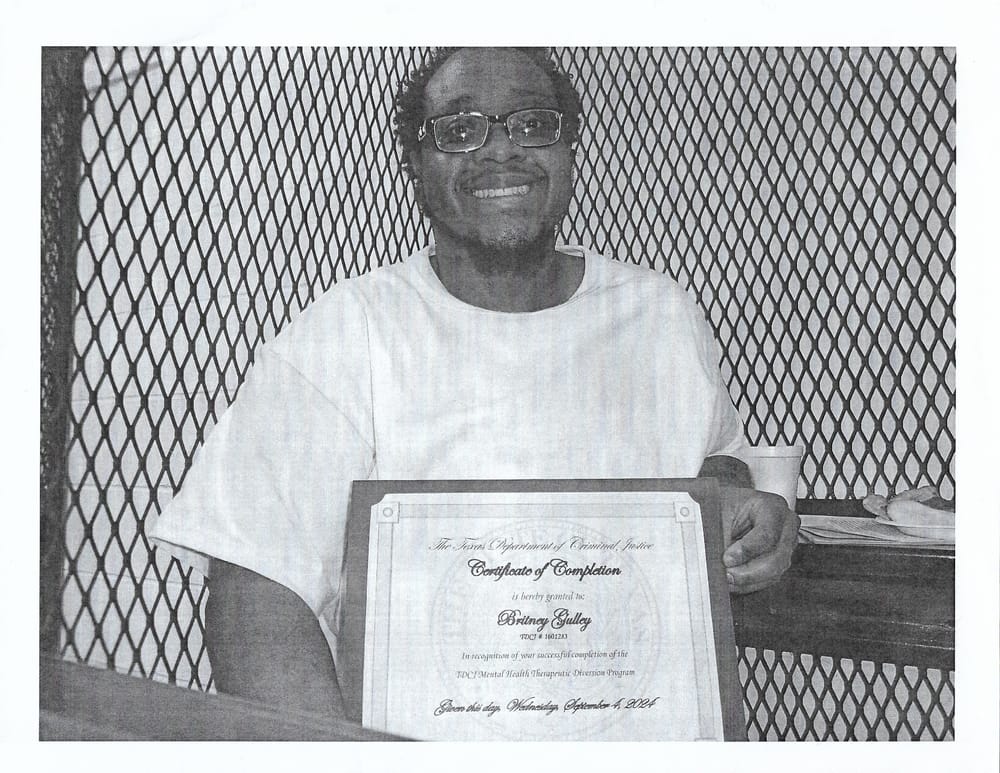

Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU) provides a number of examples of Scott’s donations bearing fruit. Of her 2020 $50 million gift, $10 million went to providing Panther Success Grants to assist juniors and seniors impacted by COVID. If PVAMU gave out the maximum grant amount to every eligible student, then that means 2,500 students received financial support—this is the equivalent of an entire graduating class.

Other downstream consequences of Scott’s initial donation include the Toni Morrison Writing Program and the PV Cares Program. The Toni Morrison Writing Program, established in 2021, currently features a writing contest for high school seniors and “an annual Writer-in-Residence who will offer public readings, master classes, lectures, class visitations and critiques of students’ works.” Established in 2023, PV Cares provides integrated academic, financial, and career support to PVAMU students. This program has been credited as contributing to two consecutive years of record-breaking total student enrollment.

On another note, some unknown quantity of Scott’s gift became part of PVAMU’s now $140 million endowment. Of that $140 million, PVAMU spends about 7 million a year (assuming spending habits similar to most other universities) while the rest is left in investments intended to grow the endowment over time.

There is a catch, though.

As the publication HBCU Money points out, PVAMU itself does not control its endowment. That is the purview of UTIMCO, a not-for-profit corporation that manages the endowments of the entire Texas A&M University and University of Texas systems. PVAMU’s nine-figure endowment is a drop in the bucket compared to UTIMCO’s $70 billion portfolio. “Good business sense” would suggest that the flagships get most of the attention. Ironically, Scott’s stipulation-less gift, meant to give the University more freedom to decide its fate, may have actually impeded PVAMU’s agency insofar as placing the money in the endowment is to place it out of reach.

So it’s sticky. The situation elides easy answers; Prairie View A&M’s case paints a positive, but caveated, picture. I would guess that the same could be said for any number of the recipients of Scott’s generosity. To be honest, I’m still skeptical. Though the guilt has been replaced with hope? Appeasement? If nothing else, then at least some belief that this particular instance of philanthropic brouhaha will mean something.

Popular Posts

Recent Posts