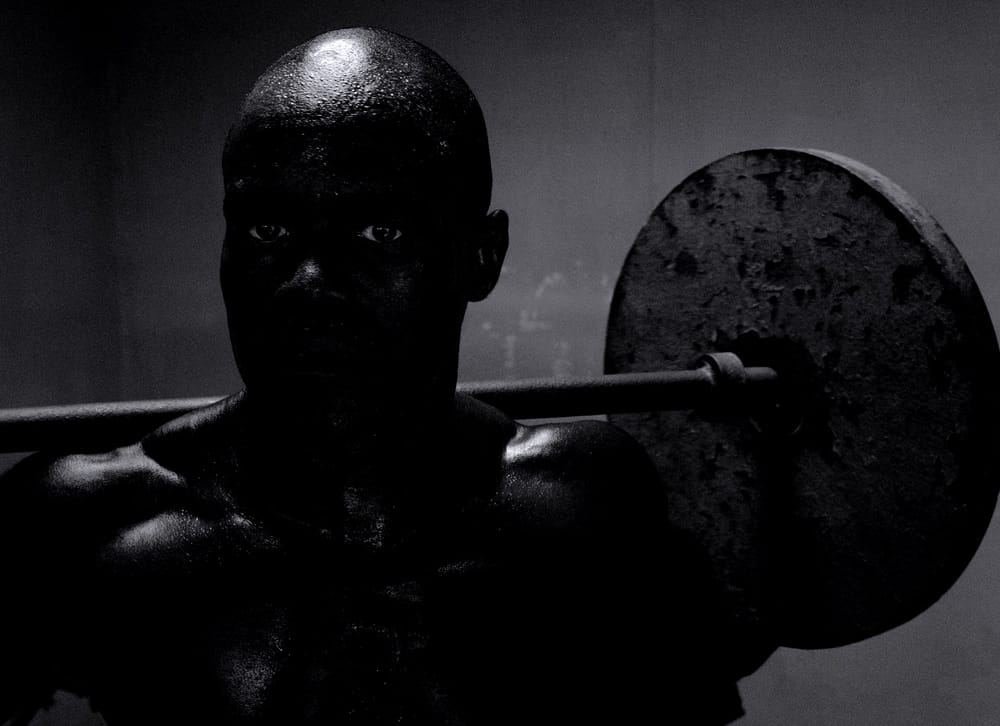

There’s a long, ugly tradition in this country of putting Black death on display. The spectacle is not new. It didn’t begin with shaky iPhone footage or hashtags. Long before cell phones, there were lynching postcards. People mailed them like souvenirs—smiling white faces in the foreground, mutilated Black bodies in the background. It was both a warning and a celebration, an announcement that our deaths belonged to the public.

That history never ended. It just shifted platforms. The postcards became viral videos. The mob became the comment section. And the spectacle continues.

For some, it’s trauma porn. A chance to watch us die again and again, to satisfy some sick curiosity, to rehearse outrage without ever having to move toward justice. For others, it’s a reason to look away. That’s me. I don’t need to see it to know what happened. I don’t need the tiny details, the body angle, the final words, the timestamp on the footage. Those details live in my blood already. They live in all of ours. Because this death is never the first. It’s always a copy of a copy of a copy.

Travis McMichael, Greg McMichael, and William Bryan are just three George Zimmermans. And Zimmerman was never new either—he was born from a long line of white men deputized by whiteness to patrol Black life. Men who knew that killing us could make them heroes in some eyes. When Ahmaud Arbery was hunted down, when Trayvon Martin was stalked, the story wasn’t original. It was a rerun.

And so when another video circulates, my first question is not “What happened?” I already know what happened. My questions are simpler, harder, sharper:

- Whose hands ended their life, and who taught those hands they had the right?

- What story is being told to excuse the killing, and who benefits from that story?

- Where is the lie, and how quickly will it be believed?

- Who gets to grieve in public, and who gets put on trial even in death?

- Which institution will shield the killer this time—police union, courtroom, media spin?

- And whose silence makes the killing possible again?

Because I know the story behind the story will sound the same: He looked suspicious. She was too loud. They resisted. They moved too fast. They moved too slow.

It’s always the same. The victim becomes the villain. The killer becomes the one “in fear for their life.” And the spectacle becomes the proof—the footage shown in court, on the news, in the feeds. Meanwhile, families are forced to watch their loved ones die in public, over and over, their grief consumed like entertainment.

I think about Mamie Till insisting the world see her son’s face. That decision had power. It was protest. It was strategy. But that’s different from the endless stream of unsolicited videos we scroll past now. Back then, it was one mother’s choice to force America to look at what it had done. Now, we rarely ask the families what they want before the footage floods the world. And too often, those images serve everyone but us: white liberals searching for moral clarity, academics looking for think piece material, media companies hungry for clicks.

I remember being in Ferguson, protesting the murder of Mike Brown, when the talk about police body cameras got heavy. Even the president pushed an initiative to fund the increase in cameras, and folks thought this was a move in the right direction. But having grown up under a government and police force that were never held accountable, to me, it felt like the only thing that would come of it was that we’d see more Black folks being murdered—just now from different angles. It turned into first-person POV, like a video game. More footage, more spectacle, but the same result: no justice, just another way to watch us die.

What gets lost is that these are not just stories—they’re lives. Lives stolen, lives replayed, lives flattened into symbols. What gets lost is that every new spectacle rests on a grave that looks too much like the last one.

So I look away. Not because I don’t care. But because I already know. I know enough to name the pattern. I know enough to resist the lie that each case is unique, that this one will finally break through, that if we just see the horror clearly enough, something will change. I refuse to let the spectacle make me numb. And still, I keep fighting—in the ways I know how, in the ways I’m asked, and in the ways I can. Sometimes that means showing up in the streets, sometimes it means holding space for grief, sometimes it means writing words like these. Looking away from the spectacle doesn’t mean surrender; it means choosing to spend my energy on life, on resistance, on making sure the story of us is bigger than our deaths.

Black death has always been public in this country. But Black life—that’s the thing we have to guard, tend to, and insist on keeping sacred.