Hypertension is a physical condition that can be exacerbated by chronic stress, depression, and anxiety—all of which are a routine part of prison life.

So, I wasn’t shocked when a visit to the prison nurse revealed that I had high blood pressure. But rather than go on medication immediately, I wanted to try to control it through regular exercise. So far, I’m happy to say it’s working, physically and psychologically.

This all started six months ago when I was sitting in a plastic chair in Washington Corrections Center's medical building, in a tiny room that was cold and bright, with a faint scent of hand sanitizer. The nurse asked me to step onto the electronic scale. The small digital screen flashed a few times before settling on 170 pounds, which the nurse recorded in a three-ring binder that had my name and prison number on the front. I stand 5 feet 7 inches tall, and that was 10 pounds over my usual weight. Having gone two years without much exercise, I knew I was out of shape.

Next up was a blood pressure reading. She slipped the sleeve onto my arm, secured the Velcro, pressed a few buttons, and the sleeve tightened. When the machine beeped and the sleeve loosened, the nurse gave me an unsettling look. "Your blood pressure's too high," she said.

The nurse immediately offered me high blood pressure pills, which didn’t surprise me. During the 16 years that I've been incarcerated, I've watched prison staff hand out medication like candy. When the call for "pill line" blares over the intercom, a lot of incarcerated men move toward the white-and-blue shed outside the living units to pick up a variety of pills. Some of those medications are, of course, crucial to treating physical conditions. But for some of those prisoners, the pills help them escape the depression that is so common inside. I don’t question others’ decisions about how to cope, but I didn't want to become dependent on medication without learning about other ways to manage my health. So, I respectfully declined.

The nurse explained that high blood pressure is common among African Americans and can lead to heart attacks, strokes, and other potentially deadly complications. Got it. But what are some of the causes of high blood pressure? I asked. Along with heredity, she explained, stress, anxiety, depression, and sodium can be contributors.

I wasn't consuming a lot of salt, but prison life produces lots of those mental-health challenges, especially the ache of being physically separated from my family. With decades left to serve on a 63-year sentence, I feel stress and depression that often seem inescapable.

And out of fear of being seen as weak by others in prison, I had learned to hide these feelings, not realizing that such emotional repression could kill me.

I asked the nurse about alternative ways to reduce the stress and depression that was elevating my blood pressure. Her response was simple: try exercising regularly. I hadn't exercised in years, but I told her that I was willing to try to avoid taking medication. She let me know that I would have regular appointments to monitor my blood pressure, and if I failed to get it under control, she would require me to take the pills.

Challenge accepted, and I began preparing myself for the hard work ahead.

Before developing an exercise plan, I began searching for a workout partner who could encourage, motivate, and hold me accountable on days I felt like giving up. When my childhood friend Carlos Bernardez committed to a regular workout regimen, I was ready to go to work.

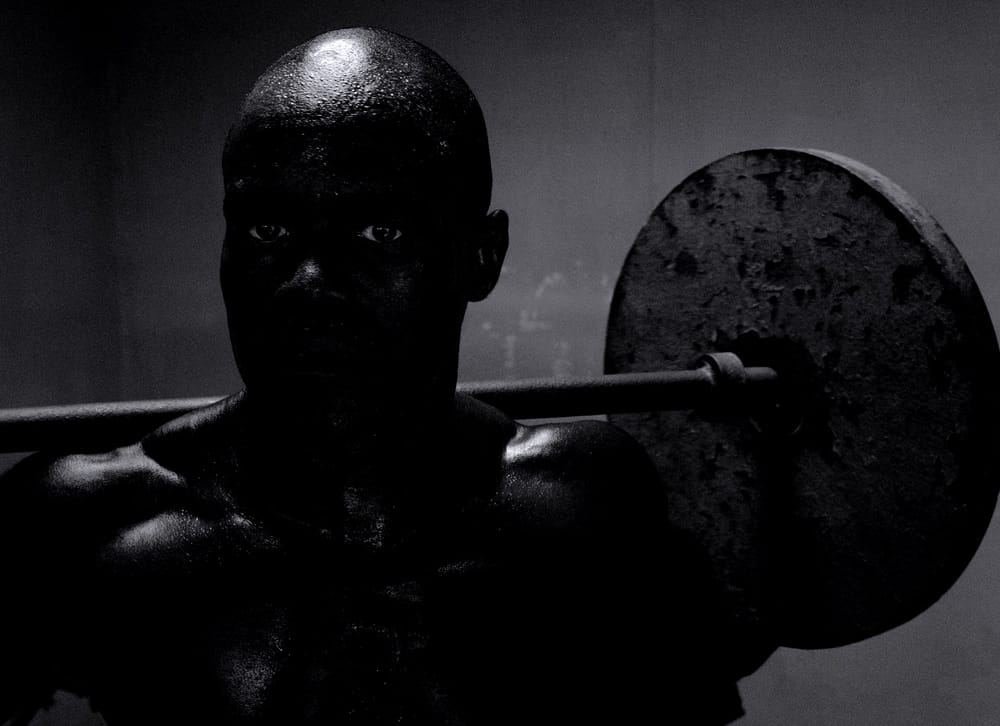

On a Monday morning, we entered the weight room to the sound of human grunts and clanging iron. A lot of the incarcerated individuals were wearing tight shirts that displayed their bulging muscles, indicating they had been exercising for a long time. Fighting off the urge to compare my undersized biceps, I reminded myself that the goal was getting healthy, not becoming the strongest man in the prison. Once we found an open area to exercise, we were ready for day one: bench press, the exercise that strengthens the chest muscles.

The following morning was a struggle. The soreness in my chest tempted me to abandon my workout plan. But after dealing with the excuses I invented to quit, I made my way back to the weight room for day two: squats, which strengthen leg muscles.

After the first week of exercising my chest, legs, arms, back, and shoulders muscles, I barely wanted to get out the bed over the weekend. But Monday morning I was back in the weight room.

Weeks turned into months, and when my body became acclimated to exercising regularly, I added a mile run to my workout regimen. Running was also a challenge, and at first, I alternated between running and walking laps around the prison yard. Eventually, I was able to complete a mile running.

Although my first few months of exercising didn't change my physical appearance, I could feel a significant change in my emotions. I felt energized, my thoughts were clearer, and the stress and depression I had become used to were lessening.

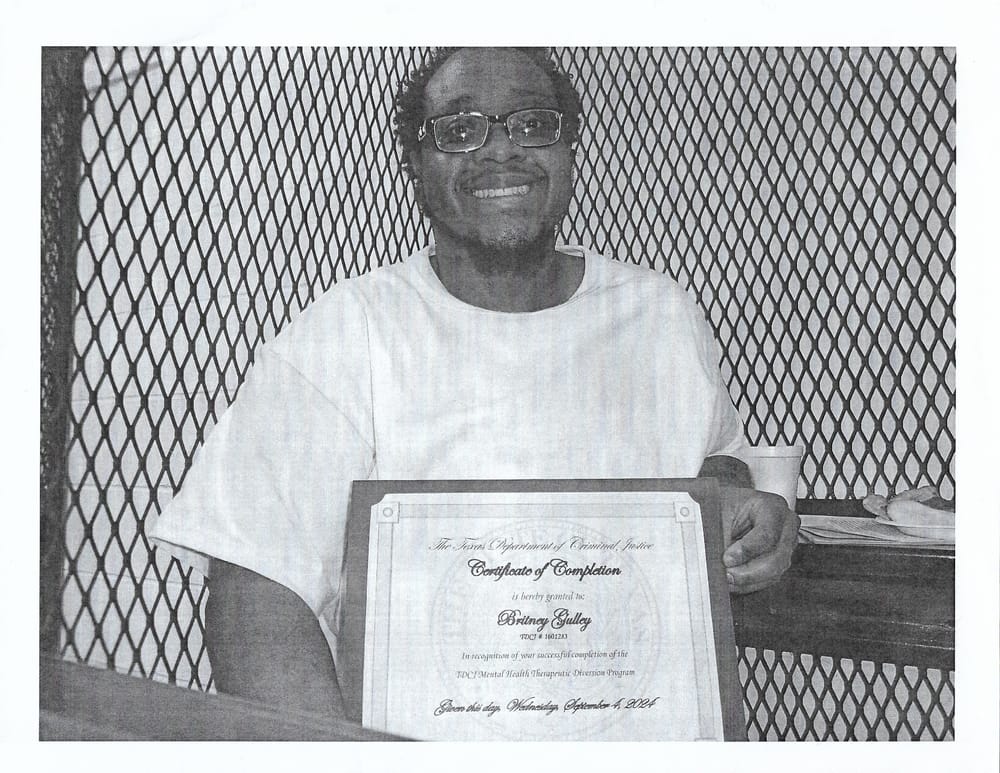

Six months into my exercise program, I was back in the medical building's steel and concrete waiting room. The prison guard signaled it was my turn, and a new nurse told me to have a seat while he flipped through the same three-ring binder that contained my medical records.

While I sat in the same plastic blue chair, this nurse reached for his stethoscope and politely asked to check my breathing. I took a few deep breaths. No problem there. Time to check my blood pressure.

As he placed the sleeve on my arm, I felt anxious but reminded myself that I had done what I could to get healthy. The nurse pressed a few buttons on the electronic machine, the sleeve tightened around my arm, and then loosened, as I hoped for the best. The nurse nodded his head in approval—my blood pressure was great, and I wouldn’t need to keep coming back to get it checked. I was relieved.

Along with the physical benefits, successfully reducing my blood pressure under the stressful and depressing conditions of prison gave me a sense of accomplishment, a reminder that even while incarcerated, I can take charge of some aspects of my life. I realized that I couldn't expect others to care more about my health than I did. When that first prison nurse had warned me of the risks, I am so glad that I chose to take control of my life and not give in to the urge to give up and take a pill. More than ever, I realize how physical and mental health are connected.

All those lessons learned apply outside of prison as well. The physical and emotional challenges of life in prison are unique, but stress and struggle are common in this world. I faced problems before I went to prison, and I’ll face them after I’m released. Being here has made one thing clear: We all get only one body, and we have to live with the consequences of how we treat it.