Table of Contents

Rather than supporting calls from among Black political movements for radical redistribution of an existing tremendous national wealth, power was redefined away from political power, and redistribution, and toward consumption. – Dr. Jared Ball, The Myth and Propaganda of Black Buying Power: Media, Race, Economics

The conflict is not just between rich and poor, not just between one generation and another, but between different concepts of what a human being is and how a human being should live. – Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs, Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century

Since his dim-witted “Liberation Day” launch, President Donald Trump's tariff proposals have brought pain to some Black entrepreneurs. In Black business hubs such as Atlanta and Chicago, Black entrepreneurs have had to freeze hiring, lay off staff, raise prices, and/or consider going out of business altogether.

Tariffs, taxes on imported goods, raise the price of doing business for entrepreneurs who need commodities from foreign countries.

Sadly, Trump's tariffs serve as another reminder that Black capitalism exists in the same globalized economy as everyone else. Black entrepreneurs wrestle with supply, distribution, currency fluctuation, interest rates, loans, staff wages, etc., like all other businesses, with the added limitations white supremacy places on their bottom line.

The allure of sovereignty gives Black capitalism its appeal. This appeal has a tendency to generate a narrow nationalist sentiment that largely neglects the role of a global political economy. Under Black capitalism, tariffs and trade deals are policies the white gods negotiate above us while we buy Black and consume our way to freedom in the kids' corner.

Thus, Black capitalism is kids' corner economics fronting as self-determination.

Can Black capitalism cure racial injustice?

The injection of tariffs and trade into the public discourse heightens the contradictions of the Black capitalist mythos, which were magnified following the 2020 police murder of George Floyd. Following the alleged “racial reckoning,” capitalists made big promises–generational wealth, financial freedom, and economic independence–positioning Black capitalism as the State-laundered solution to the problems of police brutality, wealth inequality, and opportunity. With enthusiasm and glee, Black capitalism received the backing of the White House, multinational corporations, and the Black misleadership class.

This propaganda was so effective that in at least one survey, Black people ranked supporting Black Business as the second most “extremely/very effective” solution, higher than “protesting” and “volunteering,” as a solution “for helping Black people move toward equality in the U.S.” Only “voting” trumped it. It need not matter that, as late as 2020, Black businesses made up only 0.3% of all business revenue in the US or that Walmart generated more revenue as a single business than all 3 million plus Black businesses combined in 2020. Black capitalism was the path to liberation.

This logic, although deeply flawed, was an understandable conflation for the Black masses to make. Black capitalism via Black business is marketed as a symbol of Black autonomy in a world where little exists. Who would not support Black business if it truly empowered us to control our neighborhoods, protect the George Floyds from police terror, and provide for our families? Nonetheless, Black capitalism fulfills none of these deeds.

Black capitalism rests upon two primary myths: the circulating Black dollar and Black buying power.

For purposes of this essay, in honor of National Black Business Month, we will use tariffs and trade to highlight the contradictions and limitations of each myth while decoupling the legitimate sentiments that may drive us to support them.

The myth of the circulating Black dollar, explained

Wander through any litany of Black spaces–barber shops, salons, churches, block parties, financial literacy classes, radio shows, finance bro pods, and/or social media circles–and one will likely hear some version of the proverbial “circulating Black dollar.”

Keep wandering, and one may hear how we need to “get like the Jews” or “support each other like the Chinese” or to be like whatever other ethnic groups we perceive to have more unity than Black folks. At the heart of it is a fairly noble idea: the Black dollar should “stay” in the Black community for our own enrichment and not be spent elsewhere.

The myth is not limited to random chit-chat while waiting for a haircut either. Different renditions of the claim have been voiced by best-selling Black authors, Black journalism, Black banks, and even Black politicians, often citing it in interviews and town halls full of Black folks.

The circulating Black dollar was given its wobbly foundation by financial advisor Brooke Stephens in her 1996 book Talking Dollars and Making Sense: A Wealth Building Guide for African-Americans. The claim emerges on page 18 without citation:

John Wray, an economic development specialist in Washington, D.C., did a study that traced the flow of dollars through comparative ethnic communities. Wray found that in the Asian community a dollar circulates among the community's banks, brokers, shopkeepers, and business professionals for up to 28 days before it is spent with outsiders. In the Jewish community, the circulation period was 19 days; in the WASP community, 17 days; but in the African-American community–6 hours!

When confronted about the source of her claim by Truth Be Told News, Stephens could not remember the name of the study, let alone offer any proof that the study existed. Truth Be Told found no record of it in any research database or publication. The same absence of existence is true for the alleged author of the study, John Wray.

Even if proof of the study could be found, the claim still falls on its face. In terms of ethnic groups, there is no Asian community. There are US neighborhoods populated by Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Indians, and other ethnic groups from Asia, but each group carries its own history, class stratification, and vast differences that cannot be synthesized into one flattened community (ex., Japan colonized half the Asian groups listed).

For White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) and Jews, there is no proven method for tracking the spending habits of religious groups. Plus, with 92 percent of Jews now identifying as white, the distinction between WASP and Jew is not what it was in the early to mid-20th century. For example, today, factions in both camps actively collaborate on a genocide.

Additionally, the term community connotes no geographical boundaries. Are these specific neighborhoods? Zip codes? What constitutes a Black community? 60% Black? 90% Black? Neither she nor the apostles of the claim ever provide us with the metrics to know. Each group is presented as a floating, classless monolith, with Black people serving as the worst off.

Carrying on with her baseless analysis, Stephens provides no metric or definition for her central point: circulation. No explanation of circulation as an economic basis is offered. No economist uses the term in the way she vaguely explains it. A basic understanding of trade–free or fair–teaches us that dollars are constantly in circulation. Goods could not move from one side of the earth to the other if capital weren't in motion. Thus, dollars don't necessarily “stay” in communities. They move in and out of them to circulate the goods we consume. This is the case because, regardless of race or ethnicity, most US communities do not produce all that they consume in their neighborhood.

To illustrate the point, say I need shrimp, tomatoes, and avocado for a dish, whether I go to a Black-owned grocery store or a WASP-owned Walmart, these commodities are not grown in the stores’ backlots.. They are imported. It's more likely they were shipped from India and Mexico than the US, regardless of whether I bought them at a Black business or not. Hence, nobody's dollar stays in their community for 28, 19, or 17 days. Instead, a portion of the dollar leaves the neighborhood almost instantly to pay for the entire supply chain that brought the products to the shelf.

The same reality rings true for any business that relies on imported goods. No amount of financial literacy or buying Black can overcome where items are shipped from. This is proven whether that be the sew-in weave shaved off the heads of poor women in Cambodia, only to be sold at the Black-owned hair salon; the chic clothing developed in Bangladesh, now for sale at the Black-owned fashion store; the copper conductor made in China, deployed by the Black-owned electrician firm; the white liquor containing a fermentable sugar source from Brazil, now sipped at the Black-owned bar. When Trump slaps tariffs on products from any of the countries listed, our pockets are further squeezed because most companies in the supply chain pass the cost onto the consumer. This is true even if the “banks, brokers, shopkeepers, and business professionals,” and consumers are Black.

US-led imperialism has made us all vulnerable to these market realities. The undying appetite to expand capital into cheaper markets explains why more commodities are not made at home. . White capital decided decades ago that neo-liberal free-trade would be the rule of the global economy. They pushed the backbreaking trade deals that led to deindustrializing manufacturing, offshoring jobs, and building up a carceral state to house the surplus labor created by imperialism. As an internal neo-colony in the US, Black people are all but powerless to these policy shifts. So when sections of the capitalist class decide they do not like the deals they cut with the rest of the world, Black people are some of the most likely to suffer.

Instead of offering a sober analysis on how to navigate this exploitative economy, Black capitalism relies on rudimentary concepts disguised as economics. So basic economic activity, such as trade and tariffs, gets mystified into counterfeit claims like “circulation.” Black capitalist myths like these alienate us from our labor. Rather than nationally oppressed workers who help keep the entire global economy in motion, we are reduced to neo-liberal consumers and aspiring business owners confined to declining DEI subsidies and tepid boycotts. Let Black capitalism tell it, we share nothing in common with the oppressed people of Bangladesh, India, or Haiti who enrich the stores we patronize or boycott. Hence,

Black capitalism stifles solidarity by severing us from the oppressed across the globe.

However, although a myth, the circulating Black dollar still demonstrates a desire by our people to do something. It's a recognition of a glaring contradiction where Black people produce wealth but rarely benefit from it on the same scale that we generate it. It's understandably embraced as a corrective to our inferior structural location under capitalism, but a poor mechanism for doing so.

The Black buying power myth, explained

The second folktale, Black buying power, is alluring for similar reasons as its mythological cousin, the circulating Black dollar. It proclaims Black people possess a vast faucet of wealth that we fail to tap into due to our slippery spending. Thus, Black Buying power stands as “evidence” of all the “Black dollars” we have to “circulate” into our communities, if applied.

Each year, reports are released by three marketing data firms, the Selig Center for Economic Growth, Nielsen, and McKinsey & Co., detailing Black spending habits and interests. Of course, no mention is made in these reports to the trade deals, tariffs, or any global market shifts that affect the earth. Instead, based on questionable calculations and projections, a collective buying power number is assigned to Black people. Upon publication, Black media outlets promote these reports as assessments of our economic condition by headlining the big fat buying power number:

Headline: "Report: Black Consumers Have $2 Trillion In Buying Power"

Headline: "The Power of the Black Community: How Brands Can Tap Into $1.4 Trillion in Buying Power"

Headline: $1.98 Trillion Black Buying Power

As defined in their own literature, “buying power is the total personal income of residents that is available, after taxes, for spending on virtually everything that they buy…” This does not account for the money that people borrow or the debt they accrue. Also, buying power does not “measure wealth.” So even if we accept the numbers (which we shouldn't), spending power is simply every penny we have to our name.

If we just break up the percentages of Black median household income into rent (30-40%), childcare (25%), and food (17%), we have already lost nearly 80 percent of our (buying) power. Black buying power essentially disappears if we add debt to the equation. Furthermore, the big fat buying power numbers are not solely based on income, but unreliable projections like population growth and educational attainment. This means many Black families are likely living check-to-check or worse, which is much more consistent with the eye test than the powerball numbers we call buying power. If buying power is the jackpot I guess circulation is the means to hitting it.

If buying power is the jackpot I guess circulation is the means to hitting it.

In his seminal text, The Myth and Propaganda of Black Buying Power: Media, Race, Economics, media studies scholar Dr. Jared Ball details how the term buying power originated from the Bureau of Labor Statistics during a time of labor unrest, used to describe a “measurement of what workers could buy” while keeping wages low enough “to assure maximum profit for ownership while sufficient enough to buy what was produced.” Therefore, buying power was a means to assess if workers were paid enough to purchase what they produced. This meant capitalists needed to pay workers enough to consume their goods but not enough for their workers to overthrow them.

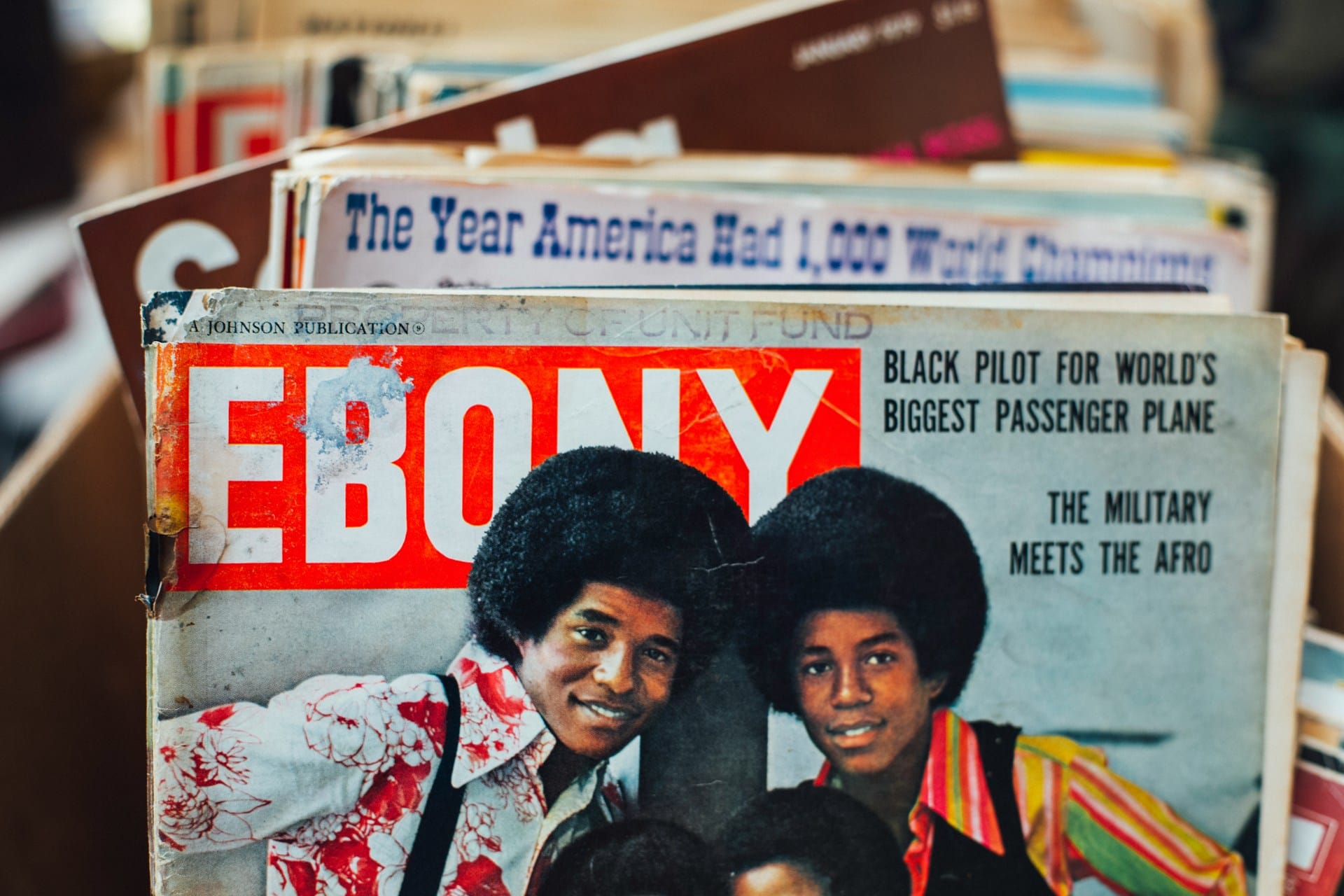

Post-World War II, Black capitalists laundered Black buying power through a marketing campaign to attract white corporate ad dollars. In 1954, John H. Johnson, the founder of the Black-owned Ebony and Jet magazines produced a marketing video called Selling of the Negro, which depicted Black people as respectable reliable consumers who were safe for white advertising. This was in a period when white corporations were leery of “circulating” advertising money in Black communities so they needed some convincing that Black folks were “good for business.” With the help of then head of the Department of Commerce Sinclair Weeks, this long form commercial utilized the labor term to launder Black consumption, assigning $15 billion in buying power at the time.

Selling the Negro emerged during the same year as the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that legally overturned public school segregation. This was during a time when integration became a US national security issue. The US government was attempting to combat the global spread of communism, so it manufactured racial progress for the purpose of demonstrating the superiority of capitalism/liberal democracy to the decolonizing world. Thus, as Ball notes, images such as those of Selling the Negro were flipped to help recolonize the African world through a veneer of racial progress that primarily benefited a small Black elite. This corresponds with what historian Gerald Horne calls the “Great Compromise of 1954”:

At the same time that there was retreat on the class front, there was an ad‑ vance on the “race” front, for in the midst of a curtailment of civil liberties, civil rights were expanded. However, the “Compromise of 1954” came with a heavy price compelling the Black liberation movement to throw overboard its most militant and class‑conscious warriors.

Thus, Black buying power as we understand it today, finds its footing during an era of escalating counterinsurgency. This era sought to launder Black Rage into consumptive practices and upward class mobility to counter a class-based Black militancy. As Dr. Ball comments, “Buying power would also become a crucial part of the mechanism of managing Black rage and potential up rise in the years following the release of Johnson’s marketing product.” Hence, Black buying power—more broadly Black capitalism— is still a go-to tactic by both the Black elite and the overall capitalist state when their legitimacy is in crisis (see 2020).

Make no mistake, the Black elite are rarely interested in a serious economic agenda. That's not their counterinsurgent role. As African psychiatrist and philosopher Franz Fanon said of the national bourgeoisie in The Wretched of the Earth,

“When such parties are, questioned on the economic program of the state that they are clamoring for, or on the nature of the regime which they propose to install, they are incapable of replying, because, precisely, they are completely ignorant of the economy of their own country.”

Still, to hide their ignorance, the Black elite will use Black buying power to invoke a nationalistic sentiment like “if we were a nation we would be the 15th largest economy.” Dr. Ball reminds us there is no “sovereign pool of wealth” we can all access. Plus, a sovereign nation-state would have the power to negotiate prices with other nations, strike deals on trade that bring in key commodities for development, tariff foreign industries to grow our own industry at home and create our own currency. Buying power dictates none of these matters.

Again, the global economy quietly fades to the background in the Black capitalist equation as our “power” is reduced to consumption. Consider the six global supply chain phases: raw materials, supply, manufacturing, distribution, retail, and consumption. If we follow the logical conclusion of buying power acolytes, our power lies in the last phase of exploitation. The phase after raw materials are extracted from the earth, refined, packaged, shipped, and sold to retailers. Then somehow our power swoops in at the shelf to kick off the revolution. The trade deals that facilitated the prices or the tariffs that privileged one product over another need not concern us. Our buying power has no power; collectively, we are broke! Yet, this is the kids' corner economics Black capitalists and their white corporate sponsors want us to follow.

The most devastating role of Black capitalism is to reify the man-made laws of capitalism as seemingly natural to us. Thus, to the Black capitalists, there is no supply chain. No trade deals. No tariffs. Things just magically appear in stores or on stoops. Nobody stocked the shelves or drove the items to the front door. Nobody had to pee in a bottle to deliver them on time. Nobody died mining the diamonds for delivery. Nobody was assassinated while organizing a union just west of the country where they were mined. Nah. These horrors are simply the consequence of a natural order that we can do nothing about. Nothing at all.

They cannot be effectively protested, resisted, or transformed. They just are. Capitalism thereby becomes gravity. So, of course, the problem is not capitalism itself but a lack of Black participation in it. Hence, why buying power is fetishized as an activity completely devoid of our labor. We apparently have no role in how commodities are made, just bought. Our “power” is vested in what we consume as if we played no role in producing it. Capitalism is natural law, so of course consumption is the only logical path to power.

Black capitalism stands in the way of real self-determination

The "natural" laws of capitalism hijack a relatively fair question, What should we do with our expendable income? and launders it into myths that bleed us for more money we do not have. They naturalize us to the kids' corner, shutting off the smarter parts of our brain while selling liberation to the slower side. Of course, these myths benefit the Black elite who wilfully pimp the slower side to get a cowering cut. They certainly benefit white capital as it allows them to continue carving up the world while we fight over b.s. that keeps us far off the scent of our plunder.

Tariffs or trade deals are not just natural laws that happen to us. In their current form, they are a reflection of unequal social relations that human beings have constructed. Thus, no matter how insurmountable they may feel, these social relations can be reconstructed through struggle to benefit us all. The same self-determination we endlessly pursue through Black capitalism can be reapplied towards socialist ends. We just have to shake off the myths.