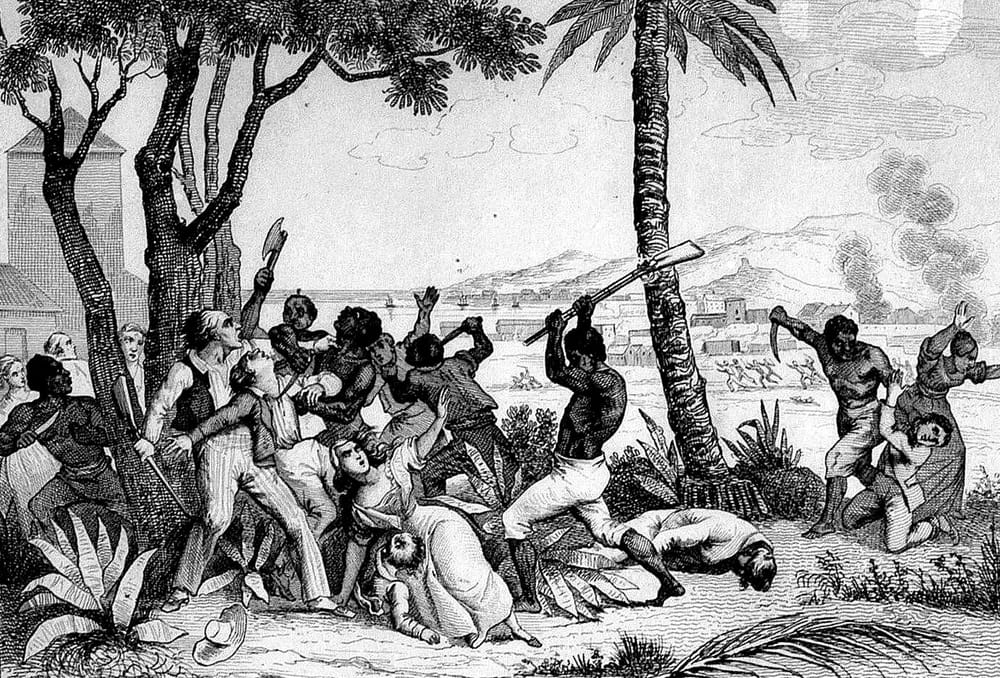

The Afrikan Offensive in Haiti, within the context of the burgeoning capitalist world market and global political economy, dominated by the relationships of different rulingg elite groups with converging and diverging interest-value constellations, as well as the interests of the subjugated, found itself as a major player within the power dynamics and struggles of the core states of the West as they tussled for control in the Atlantic world. Here we will focus on U.S. interests characterized by the American ruling class trying to solidify its government, trying to expand in order to survive, and grappling with the race/slavery question which events precipitated by the Offensive in Haiti, like the Louisiana Purchase of 1804, intensified. A special interest will be afforded to Thomas Jefferson and his influence as secretary of state from 1791- 1793, and president of the Union from 1801-1808, whose particular ideology and vision – Jeffersonian Republicanism – requiring land for all white males, a nation of small independent “farmers,” called for no income tax, and a small federal military provided a foundational framework for an important period in the development of this country and region.

In a stroke of irony that can only be observed in retrospect, on the 30th of August 1791, Jefferson wrote a letter to the famous Afrikan scientist, watch-maker, and city planner, Benjamin Banneker. Within the letter, Jefferson assured Banneker that nobody wished “more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind [Afrikan bondmen and women] to what it ought to be.” Eight days prior, Afrikans in Le Cap, St Domingue rose up in an attempt to “raise their condition” on their own accord.

Jefferson, architect of the U.S. Constitution, chief among the liberal bourgeois intellectuals of the American Revolution and post-Revolutionary period 1776-1810, understood the hope of his infantile “American republic” project lay in its territorial expansion and the inevitable problem of slavery. Still a fledgling nation, and facing the interests of Spanish, British, and most importantly French ruling classes, his administration's ability to consolidate American control on the North American mainland and general region and stifle any attempt by an aggressive Napoleon to mount an offensive by way of Florida was paramount. Jefferson and Napoleon did have one thing in common: they both were white supremacists that did not want to see an Afrikan state rise. Jefferson was complex and inconsistent. Both Adams and Jefferson's primary focus was the appeasement of the southern states, that constituted majority of the national export product, and to whom the Revolt in St. Domingue posed serious concerns both in its symbolic affront to antebellum civilization and in its material reverberations that stimulated people like Gabriel Prosser in 1800 to plan wide scale revolts.

Jefferson, a Virginian slaver, wrote extensively on the question of slavery and its relationship with the future of his country. Jefferson in a letter to John Adams acknowledged a "natural and artificial aristocracy." The artificial aristocracy he argues is founded on "wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents." In contrast, he considered the “natural aristocracy” to be the "most precious gift of nature, for the ... government of society." He goes on to postulate that the "form of government is best" when it "provides ... for a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government." This contradiction between Jefferson being incredibly wealthy and his appeal to the petit blancs of his nation is the cornerstone of his political success.

In 1789 a conflict against “artificial aristocracy” began in France with the subject of slavery at its core. Jefferson, staunchly anti-aristocratic, and staunchly in favor of slavery threw his support behind those challenging the “artificial aristocracy.” The trouble brewing in France's most profitable colony, St. Domingue, which began decades before the republican conflict in France, added fuel to the blazing fire. In a 1792 letter to Lafayette, Thomas laments the trouble France was having with their slave colonies and “sincerely wished for their restoration, and connection to you [France].” In the same letter Jefferson gave a glimpse into his understanding of the slave uprising in St. Domingue, less than one year old at the time. He said “no future efforts you can make will ever be made to reduce [defeat] the blacks” and that it is his opinion that “all that can be done … will be to compound [aggravate] with them” which was “done formerly in Jamaica.” The 1791 Revolt in St. Domingue presented the American government, then in the hands of the Federalist leaning Washington administration, of which Jefferson was Secretary of State, with an opportunity to wrestle away control of Atlantic markets and territory away from the French.

The French government, financiers of American Independence, who controlled 11 million acres of land west of the Appalachian mountains, as well as the question of slavery, which had not been resolved by the 7 Years War, and was growing more precarious as the country's population swelled and ached to expand westward, was presenting a serious problem for the new Union. It is important to see European-American activity on the island of St. Domingue as proxy activity in order to get the upper hand in the region. Whoever controlled St. Domingue controlled the region.

During the administration of John Adams, the American government sent various kinds of military and economic support to L'Ouverture in order to further destabilize French control of the island/region and retaliate against French naval forces who were harassing American commercial ships and severely restricting trade with the U.S. This conflict precipitated as the U.S government incurred the chagrin of the First Republic by signing the pro-British Jay Treaty of 1794, which Jefferson opposed. The aid, however, was predatory. Federalists argued that giving Haitians the food and other supplies would “free them of the necessity of commerce and navigation.” As Tim Matthewson explains “Adams had concluded that a weak, independent Saint Domingue under indigenous black leadership was preferable to a colony dominated by people he derisively called turbulent Gallicans.” Thus, it was well within the interests of the U.S. government to wrestle Haiti away, albeit covert and tact-like, from French control.

Thomas Jefferson’s administration won the 1801 election and set the tone for foreign policy towards Haiti for at least 50 years. Summarily, United States foreign policy towards St. Domingue in the initial years of the struggle included a Federalist pro-rebel policy, aimed at gaining a foothold in the island's commerce, influencing its politics, and protecting the interests of the southern states and those of U.S merchants. Embodying the interests, and more importantly, the fears of the South, Jefferson's policy of containment and isolation, marked by the Embargo of 1806 was enacted in part because of what Matthewson identifies as the “ideological threat” of the African offensive. Jefferson wanted control of Florida because of the Black Threat (Seminole War). He feared that the unruly tendencies of Afrikans in the Caribbean, where they outnumbered whites and thus kept intact their culture, would link up with the unruly activity of Afrikans in Florida and offset another Afrikan Offensive in the United States, where control of Afrikans was more complete because of the disparity in population.

In 1799, the Consulate seized power in France, establishing a hereditary monarchy with Napoleon at its head and concluded the French “Revolution.” Napoleon, inheriting a unstable France sought to consolidate control. His first move: reinstate slavery in St. Domingue. This was an intelligent strategy, seeing as France's wealth, along with that of the other Western states was founded on a colonial mode of production. Jefferson ideologically opposed to such forms of government, characterizing them as "a mischievous ingredient in government," did have one commonality with Napoleon: white supremacy. Initially, Jefferson saw Napoleon as a tool to limit British influence in the North American region, but was increasingly critical as Napoleon limited the power of the French press, silenced parliamentary debate, and held national referendums to quell independent thought.

Personal and ideological differences aside, secretary of state James Madison remarked the United States would withdraw from Saint-Domingue rather than hurt relations with France." The two nations would then cooperate to isolate and constrict the growth of newfound "Haiti." The United States passed laws to cripple the Haitian economy, as well as refusing to recognize Haitian statehood for 60 years. One piece of legislation was the Logan Bill of 1806 that prohibited merchants from trading with Haiti. The French initially did not recognize Haitian statehood, but did so in 1825 only after Haitians agreed to pay 150 million francs in "reparations."

The French, under the command of Rochambeau, were defeated in the Battle of Vertieres in 1803. Nana Dessalines declaring "independence" in 1804. Napoleon seeing no hope for an extension of his Roman-styled empire in North America without St. Domingue as an anchor, was advised to sell his Louisiana Territory to the Americans. He acquiesced and sold it for $15 million dollars. Among the far reaching benefits for the American government were the access to the Mississippi River and New Orleans Port which would have incredible effects on the influence of the United States' imperial ambitions and potential. The sale effectively doubled the size of the country and made Jefferson's vision of a nation of self sufficient small farmers more probable.

This might have been a loss for France, but it was not a loss for Western civilization and the trajectory of their modernity. Both France and the United States were together in their colonial interests. Further, American interests in Haiti can be said to be the beginning of a distinctly American imperialism manifested culturally as the symbolism of “Manifest Destiny” and politically as mandates like the Monroe Doctrine (1823) and the Roosevelt Corollary (1904) aimed at solidifying American dominance in the region.

In summary, while the Afrikans on the island of Haiti fought and resisted the British, French and Spanish militaristically, the American government, who never overtly participated militarily, manipulated the situation to their benefit. This speaks to how our “solutionizing” can work in the favor of our enemies, who are multipolar. We beat the French, British and Spanish, and ultimately aided the Americans. The United States of North America had to secure the region and containing Haiti was the first step to containing the Caribbean, Central and South America. This also shows that neocolonialism had developed in the Caribbean faster than it did on the African continent.