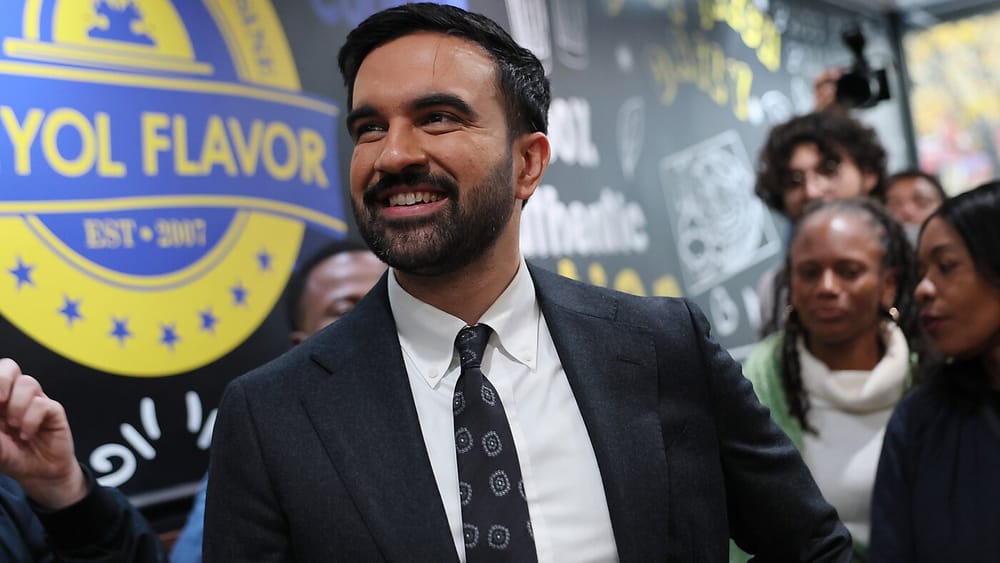

On the morning of the general election, New Yorkers and the rest of America await who will be the next mayor of the richest city in the world. Democratic candidate Zohran Mamdani and the Democratic Socialists of America, the largest socialist organization in the country, shocked Republicans and Democrats alike by setting in motion one of the most compelling political campaigns in modern New York City history. One that led to the highest level of voter participation in New York City’s 2025 Primary Election in over a decade by putting working-class New Yorkers’ biggest need, affordability, at the forefront.

The lack of working-class Black supporters for both a candidate and an organization that champions the working class mirrors the unresolved tension in the progressive promise of a multiracial, working-class coalition—the socialist wing of the Democratic Party, alongside the party itself, is struggling to earn the trust of Black voters. Despite a presumptive win for Mamdani, DSA, and working-class New Yorkers, Mamdani underperformed in the primaries in predominantly Black neighborhoods and in areas where the median income is under $62,800.

This tension is merely a microcosm of a shift in Black voter patterns from the 2024 presidential election that is underdiscussed among the relentless chaos of President Donald Trump’s administration. While 83% of Black voters supported Kamala Harris in the 2024 election, Black voter turnout was lower than in previous elections. Simultaneously, President Trump won 15% of Black voters, up from 8% four years earlier. These numbers could suggest a significant voting bloc for the Democratic Party—the Black working class—is at odds with the Democratic Party.

When speaking to DSA members within the New York City chapter, many feel Black working-class voters’ disillusionment. Ben L., a DSA Central Brooklyn branch member and field leader for Mamdani, quickly realized that the coalition capable of winning elections isn’t necessarily the one that shows up to vote.

“The problem the whole socialist movement has—not just here, but everywhere—is that the coalition we need to be a majority, or even to significantly cast power, is pretty convinced the system is all bullshit,” he said.

Ben recalled doing the most election work of his life in 2022 for David Alexis’s state senate campaign that focused on stronger tenant protections, a Green New Deal for New York, and more investment in non-policing solutions to crime. He canvassed three times a week and spoke to more than 2,000 voters. “That’s not just something you see in the data,” Ben said about voter turnout for progressive candidates. “I talked to a lot of grandmas from Flatbush who told me that.” David Alexis lost against Kevin Parker, who has held the seat for over two decades and is notorious for his violent outbursts.

To outsiders, especially those beyond New York City’s progressive bubble, that might be surprising. But for many longtime Black New Yorkers, the political promises of local and federal politicians feel, at best, familiar—and at worst, patronizing. With figures like disgraced former Governor Andrew Cuomo and current Mayor Eric Adams, it’s no wonder that older New Yorkers are skeptical. And that skepticism is earned.

Take Cuomo’s run for governor in 2010. He acknowledged that New York’s reliance on property taxes to fund education was inequitable and pledged to fully implement the Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) mandate to close the gap between rich and poor school districts. Yet a decade into his governorship, Cuomo hadn’t fulfilled that promise. Instead, his resistance to increasing education funding widened the divide. The spending gap between the wealthiest and poorest students grew from $8,623 per pupil in 2011 to a record $10,400 in 2020—a 20 percent increase. By then, New York ranked among the worst states for school funding equity, directly impacting thousands of low-income Black families.

DSA ultimately faces the same challenge as mainstream Democrats: earning the trust of Black working-class families who have been failed by Democrats time and time again. Despite a 10% increase in DSA membership nationwide since Election Day 2024 and a rapid rise in new organizing committees in cities and regions without existing chapters, the organization remains predominantly white. According to a 2021 DSA membership survey, in terms of racial diversity, 85% of respondents identified as white, 9% as Hispanic, and only 4% as Black. Additionally, only 4% of DSA members were blue-collar workers.

I, too, was considering the DSA as an alternative to the historic two-party system after the 2024 Presidential Election. As a Black Latina and born-and-bred New Yorker, the growing tension in America, fueled by the rising cost of living and grocery prices, was glaring in the city. The homelessness and mental health crisis were evident in almost every train ride home, and the misinformation and fear-mongering I constantly had to decipher for my own immigrant parents is still relentless. In an attempt to reconcile this tension, I attended a DSA 101 meeting where I found only one other Black woman my age, an older Gen Zer, and no one who looked like my mom or dad.

Black members like Sid C., another Central Brooklyn branch DSA member, talk about their path to DSA and socialism.

Raised in Minnesota, one of only two states where the Democratic Party goes by a different name locally, the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Sid explains, “I was raised by people who were very much part of a progressive, liberal tradition in U.S. politics that believed in democracy and people power in terms of building political movements, but not necessarily socialism, at least not when I was growing up.”

When asked about the lack of Black working-class DSA members, Sid said, “I think what’s actually really scarier than the fact that DSA has a whiteness problem is that all politics has a whiteness problem.”

If you take a look at voter turnout in New York City’s 2021 mayoral election alone, Sid isn’t wrong. According to the city’s Campaign Finance Board data, the neighborhoods with the lowest turnout were all in the Bronx, with just 14% of eligible voters casting a ballot in Melrose, Mott Haven, and Port Morris—each of these neighborhoods being home to predominantly low-income Black and Latino families. Meanwhile, neighborhoods with high-income white households, like Park Slope and Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn, had the highest turnout, with 44.3% voting.

“Trying to find a sincere way of moving through that is going to take a very interesting and terrifying cultural shift that I don’t know what goes into it,” Sid continued. “For me, the reason that I, as a Black person, am in DSA and am doing these things is because I fundamentally believe that this is where the act of politics is happening.”

That terrifying cultural shift was most evident when connecting with Isaac Pablo Duarte, one of the few Black members within the Bronx, Uptown Manhattan branch.

Isaac recounts how, growing up in a Dominican Jehovah’s Witness household, politics was not discussed. “They [his parents] don’t vote, they don’t like politics– they think it’s bad,” Isaac explained.

Despite his parents’ reliance on religion to navigate life’s challenges, he didn’t choose that path for himself. When Isaac attended Stony Brook University using federal and state grants, such as the Tuition Assistance Program and FAFSA, and after Bernie Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign, Isaac found his role in electoral politics and realized how important it is to engage politically to protect the social services that helped him get into college.

“It was at that point that I became civically engaged and understood the importance of being politically aware, but I realized then that the social aspect of it was really the important part.”

In 2023, Isaac became a DSA member and soon recognized the issue of whiteness within the organization. “DSA doesn't do well at all at engaging with Black people and Latinos,” Isaac said. “It is a hard thing for people to reconcile with and trust. But if I care about it being too white, I'm going to show up and make it not as white.”

When discussing the general disillusionment of working-class Black people and Latinos in the Democratic Party, Isaac spoke about his dad. Isaac had come to understand that his father’s views were shaped by his unique lived experiences, both in and out of America.

“It has a lot to do with his upbringing, moving to this country, and his other son, my half-brother, who has been in and out of the carceral system,” Isaac explained. “He wants to help his son, but the system that his son was put in made things worse, which took a toll on my dad and mom’s relationship.”

Isaac’s family dynamic is much more indicative of how the current cultural shift in Black America's voting patterns is one we can no longer predict, but rather highlight as a use case. Professor Nikhil Singh, Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and History at New York University, and author of Black is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy, shares plainly that one of the biggest condescensions of progressives is an imposed unified Black perspective.

“The assumption that there is a kind of unity or unified perspective that Black Americans share is wrong, and it’s been wrong for a long time,” said Professor Singh.

This assumption can, in part, be based on African Americans' voting history.

After gaining the right to vote in 1870, most African American men supported the Republican Party, viewing it as the party that ended slavery and championed civil rights. But following the 1877 Compromise, which restored power to Southern Democrats, African American voters were largely disenfranchised again. It wasn’t until the Great Migration in the early 20th century that African American political engagement resurged in the North, where Democrats began appealing to African American workers through labor alliances. Still, many remained loyal to the GOP until the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights in the 1960s, which cemented Black voters as a core Democratic constituency.

I shift between “African American” and “Black” voters here because this is also an important distinction. Many newly immigrated Black people from the diaspora did not live in a pre-Civil Rights America, let alone the nadir of American race relations. In modern times, Black people from the Caribbean, Latin America, and Africa immigrated to the United States between the 1950s and the 1990s, gradually evolving the political landscape of America. Dominican immigration to the United States, for example, occurred significantly during the second half of the 20th century, particularly after the assassination of anti-communist President Rafael Trujillo in 1961. Jamaican immigration also occurred primarily in the 20th and 21st centuries, with significant increases following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act.

Despite African Americans’ affiliation with the Democratic Party, many Black people across the diaspora don’t consider themselves to be leftists or liberals. In 2019, the Pew Research Center found that 25% of Black Democrats identified as conservative, and 43% identified as moderate. White Democrats remain more likely than Black Democrats to describe themselves as liberal.

Age, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and other factors are discrepancies within the Black community and our viewpoints. However, something quite obvious when connecting with Black members of DSA is that, like most DSA members, almost all had a college degree. While some Black members also had college-educated parents, that wasn’t always the case. As the most formally educated person in his family, Isaac skews more liberal than his parents. His family’s religious ideologies and immigration story led them down two separate paths—paths that disenfranchised one generation and propelled the next.

“The really big areas where Trump gained the most voters were among men without a college education, among white, Black, and Latino men,” says Professor Singh. “Trump positioned himself as the candidate of the sort of uneducated person who hasn’t gotten a fair shake, and ultimately, Trump played very well to class resentment.”

Facing structural barriers, Black men are enrolling in colleges at a significantly lower rate. At historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), Black men now make up 26% of the student population, down from an already low 38% in 1976, according to the American Institute for Boys and Men. At the same time, Black women, who lead most demographic groups in college enrollment and completion rates, are also experiencing the highest level of unemployment rate, 7.5% in August 2025, since 2021. Both of which point to the fault lines in this “terrifying cultural shift” for the Black working class.

Within the nine days of early voting, over half a million New Yorkers have turned in their ballots. A staggering jump from the less than 200,000 early voters in the 2021 general election. Whether Zohran Mamdani and the DSA will be able to make the turnaround for Black working-class New Yorkers is yet to be seen. For older Black New Yorkers, I empathize with the reluctance to change, especially as so many of our community members have been priced out of their homes and are feeling failed by whichever vote one casts. The Democratic establishment is seemingly to blame for that shift. Though socialism is the solution to our class problems, winning over working-class Black people will require much more intentional connection from political candidates, whether they’re progressives or self-styled socialists. One that does not harp on preconceived Black voter issues, but addresses this exact disillusionment and how to mediate those gaps for Black working-class people to feel that their political agency is seeing tangible results.

“My dad has given up his political agency,” Isaac shares. “What he and my mom do instead is go preaching every day to try and make some kind of change in what they want to see in the world.”

More from Grassroots Thinking

Elections

Imperialism

Most popular

Latest