“It is not enough to hate and believe in the past to make a revolution. Hatred and belief in the past are sufficient prods for the rebellion phase. We must love and be future-oriented if we wish to carry out the revolution.” ― Ghassan Kanafani

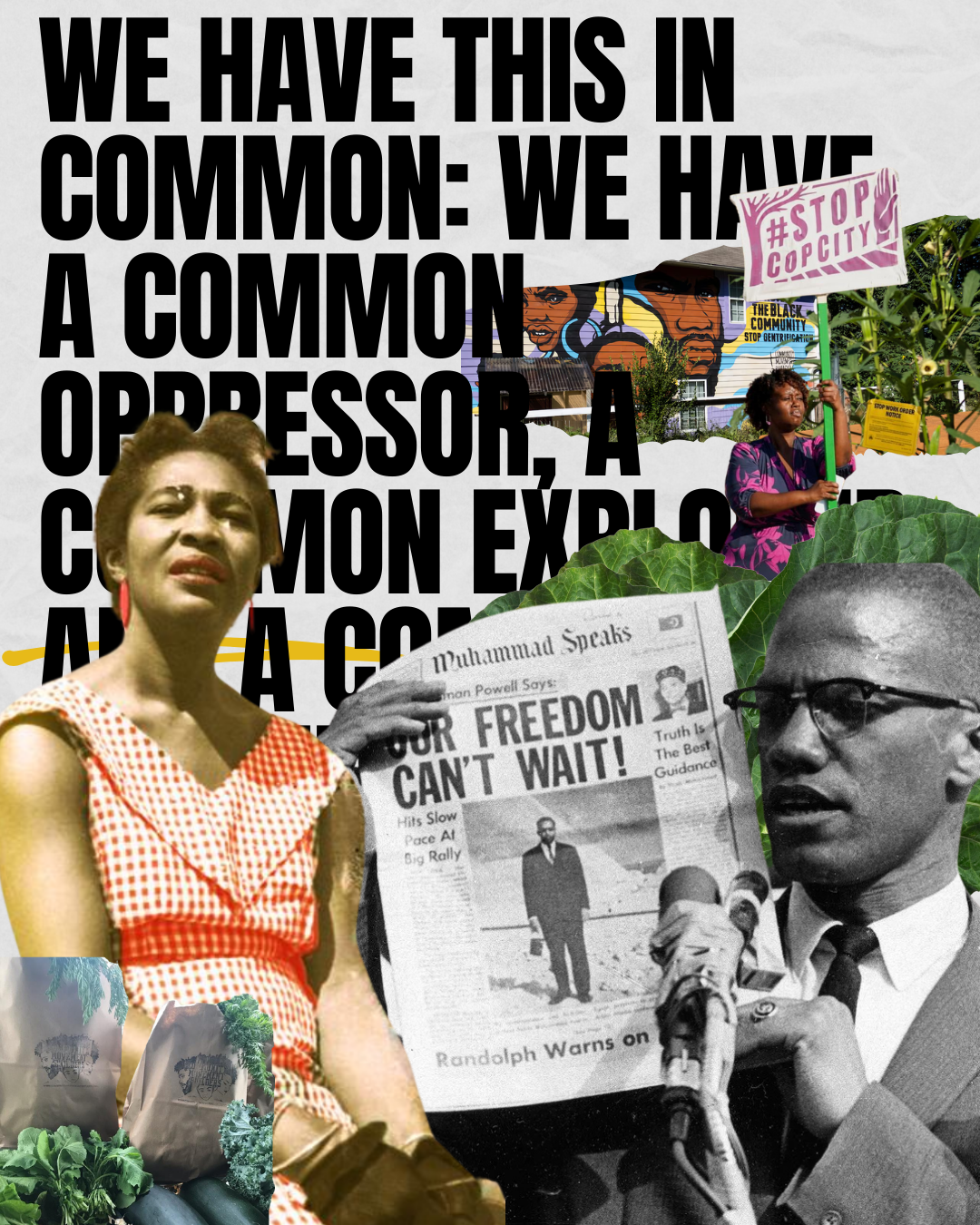

“One day I know the struggle will change. There’s got to be a change—not only for Mississippi, not only for the people in the United States, but people all over the world.” – Fannie Lou Hamer

In the previous articles in this series, we examined the necessity of rootedness in our ancestors, our lands, and our people; we then detailed the condition of neocolonialist domination that constitute the current phase of war on Black/African people in the U.S.; and finally, we explored six strategies for constructing a counter-war that might birth grassroots economies for our collective liberation. To close this series, we turn to a framework and a vision of the Black Commune that might root us in the needs of our current struggle, and build the courage required to organize and win our self-determination and liberation.

The Black Commune and Deconstructing the Neoliberal City

From August 9-13, 1971, incarcerated freedom fighters in New York’s Attica state prison asserted their humanity and dignity by revolting against the state’s war imposed on them in the form of the carceral facility, conditions, and system. They did so by taking control of their wing of the prison and establishing a temporary refuge from the everyday oppression of the state and a base of power from which to make demands. As Orisanmi Burton (2023) details in the Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt, the Attica rebels were responding to conditions of war against their humanity, and in the process of rebellion they asserted a ‘counter-humanism’ that envisioned dignity and self-determination.

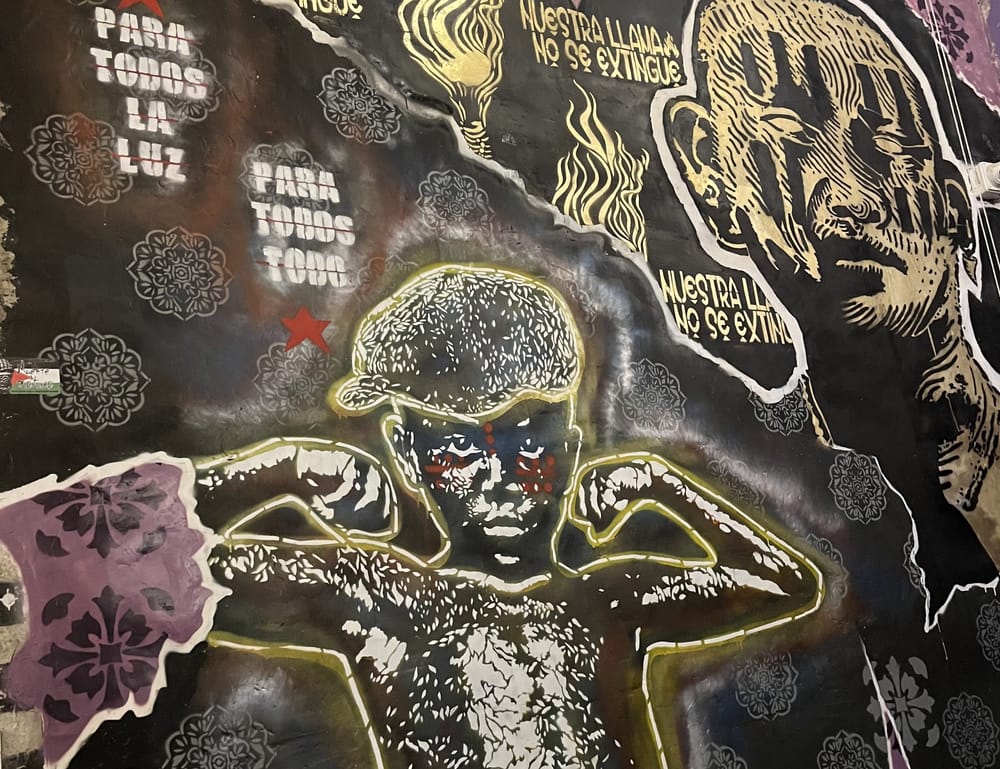

While popular narratives of the prison revolt and subsequent state-sanctioned massacre focus on the dramatic eventual violence during the siege of the prison (state law enforcement killed 39 of the 43 people who died), the critical story for us is the space of temporary autonomy and liberatory demands that the Attica rebels pursued and instituted in the process of waging a counter-war for their humanity. Burton describes this physical, social, political, and spiritual space as a form of what George Jackson called ‘the Black Commune’. Jackson conceptualized that prison was only the most intense form of an exploitative and perverse system of centralized economic power, corporatist political domination, and false democracy – a system that is mirrored across scales of imperialist plunder: the local, the national, and the global. This reality would breed inevitable revolts that might bring about destruction of the entire white supremacist, capitalist system and the prison that is fundamental to its operation, and out of this destruction, a generative, grassroots alternative might emerge: the Black Commune (Jackson, 1972).

For Jackson and Burton, the Black Commune is not just a physical manifestation toward Black liberation but is “itself a demand for a new world” and “an autonomous site of self-organization capable of nurturing revolutionary culture and alternative modes of collective life” (Burton, 2023). Attica Rebels focus during their revolt was not violent retribution, but toward fulfilling the promise of new form of humanity premised on self-determination, which they were creating for themselves, before the state’s violent incursion.

This is relevant beyond the walls of the prison and for our conversation on constructing grassroots economies toward Black/African liberation. The Black Liberation Army (BLA) theorized the Black Commune as well, as actual communes of Black/African peoples based on three principles: (1) economic self-reliance/survival programs rooted in communalism, (2) the humanization of relations among the people, and (3) the political base that would be the foundation of the New Afrikan nation (BLA, 1978). The BLA – whose members were violently pursued, jailed, and murdered by the state – premised this expanded view as part of a wider nation-building project that would emerge through armed struggle. Though most of us do not face the crushing oppression of the prison or violent state capture, we can interpret the Black Commune as a vision and a framework for countering the neocolonial war on our peoples and communities. From the Attica Rebels and the BLA, we understand that the Black Commune is not about inclusion and recognition – which are easily co-opted to serve forms of colonial domination – but survival, self-defense, resurgence, organization, and autonomy for Black/African people at a collective level, which makes possible “a space-time of ecstasy, joy, love, intimacy, pleasure, and collective Black radical becoming” (Burton, 2023).

Politics in Command to Fight Neocolonial Redirection

If the framing of the Black Commune seems strange within the context of city planning and local economic development, it is. This framing rejects the façade of supposedly apolitical bureaucratic processes and technocratic efficiency, both of which enable the neoliberal status quo of colonial domination. There is always a politics behind the decisions made in our communities. Imbuing a Black/African liberatory and revolutionary politics is an attempt to discuss how we defeat this war that we did not start, and an invitation to think about how to build collective self-determination and what DuBois called a ‘durable peace’ (Burden-Stelly, 2022) in service of our people, our communities, and our planet.

To guide this, I offer four principles that might speak to meeting the needs and desires of grassroots efforts in the vision of the Black Commune, which come from analysis of several grassroots projects I’ve organized with or interviewed (noted at the end of this piece): (1) forging a Culture of Liberation through mass-based popular struggle and collective self-actualization; (2) engaging in Social (Re)Construction through collective self-determination and unity in struggle; (3) fostering an Ethos of Community Care through communal internal healing and external solidarity; and (4) pursuing Justice in Our Life-Sustaining systems (food, water, energy, housing, education, etc.)through community-owned asset-building and relationship transformation. Enacting these principles could look like developing cultures of liberation through popular struggle and collective self-actualization, which serve as a foundation for processes of social (re)construction that have visions for self-determining communities with an ability to support unity and collective autonomy for Black/African peoples. Such processes are made possible by an ethos and everyday practice of community care both within and between communities that keep people alive and push back against exploitative, violent systems. Maintaining survival and health then allows us to collectively struggle for the transformative changes that would bring justice in the various life-sustaining systems that we require and desire. The Black Commune, in struggling against the oppression and violence of intersecting systems of oppression and struggling toward self-determination and dignity, can become the site of testing and refining such practices.

Realizing these principles, as well as the strategies outlined in part iii, requires a focus on the primacy of organizing our people and building our collective power as the basis of planning for grassroots economies. Practitioners of planning and economic development must work with, and in service of, the popular movements opposing the many faces of imperialist and neocolonial domination. How can we talk about social justice or abolitionist planning (Abbott, Aslan, O’Brien & Serafin, 2018; Dozier, 2018) but not mobilize against the dozens of Cop Cities’ being proposed and built across the country? (Johnston, 2024). How can we claim to care about the everyday needs of our people, but timidly look away from the vampiric assault on affordable housing by private equity companies and captured politicians? (PSEP, 2022).

We cannot afford for planning and economic initiatives to continue to hide behind apolitical masks and fear asking such questions because as George Jackson (1972) said, “people are already dying who could be saved…generations more will live poor butchered half-lives if [we] fail to act”.

Finding the Courage and Consciousness to Wage Counter-War

The project of constructing grassroots economies toward Black/African liberation is part of establishing new material, cultural, and spiritual understandings and relationships toward defeating the war against our people and constructing our collective liberation. When Eric Williams (1944) wrote that slavery was war, he was naming a fact that enslaved Africans in Haiti in 1791, in New Orleans in 1811, in Jamaica and Southampton County, Virginia in 1831, and in so many other places across the Atlantic world knew – that they were subjected to conditions of war, and they had to resist. The rebels of Attica understood the war conducted against them – and they resisted. The Palestinian people have long understood the 76+ year Nakba as an ongoing war on their lives – and they have resisted: the First and Second Intifadas, the BDS movement, the Great March of Return, Al-Aqsa Flood, and the everyday methods of steadfastness and rebellion.

Unfortunately, Black/African peoples in the U.S. currently do not have a mass consciousness to understand and struggle against the conditions of our own neocolonial domination – that is for us to build and to act upon. I hope that this series has contributed something toward that goal, something that will make us stronger collectively, grow our ability to defend our people and neighborhoods, and make possible the flourishing of grassroots economies in the vision of the Black Commune. It is our liberation to struggle for and our future to construct. The time to act is now.

Note: Again, I extend my deepest appreciation to the organizers and workers involved with the following projects, who were gracious in the time and space they afforded me as researched and explored the concepts that appears here: in Cuba: La Red Barrial Afrodescendiente, Afrodiverso, Mas que Ile Mas que Omo Mas que Oko, La Muñeca Negra, NaturArte, Sorpresas de Ocha, Taller Yoruba, Todo Turbante; and in the U.S.: Anti-Displacement NYC, Aurora Participatory Democracy Hub (Illinois), Black Alliance for Peace – Baltimore, Black Alliance for Peace – Chicago, Boston Ujima Project, Central Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation, East New York Restoration, Liberation Through Reading (Maryland), Ujima People’s Progress Party (Maryland).

References

Abbott, Aslan, O’Brien & Serafin. (2018). “Embrace Abolitionist Planning to Fight Trumpism.” Planners Network. https://www.plannersnetwork.org/2018/04/embrace-abolitionist-planning-to-fight-trumpism/

Akuno, Kali & Matt Meyer (2023). Jackson Rising Redux: Lessons on Building the Future in the Present. PM Press: New York.

Black Liberation Army [BLA] (1978). “Study Guide, 1977-78.” BLA Coordinating Committee. Retrieved from imixwhatilike.com: https://imixwhatilike.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/BLA-Study-Guide.pdf

Burden-Stelly, C. (2022). W.E.B. Du Bois Against U.S. Capitalist Racism: Durable Peace and the Fulfillment of People(s)-Centered Human Rights. American Communist History, 21, 3-4.

Burton, Orisanmi. (2023). Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Dozier, D. (2018) A Response to Abolitionist Planning: There is No Room for ‘Planners’ in the Movement for Abolition. Planners Network. https://www.plannersnetwork.org/2018/08/response-to-abolitionist-planning/

Jackson, G. (1972/1996). Blood In My Eye. Black Classic Press.

Johnston, Renee. (2024) “Cop Cities, USA.” Is Your Life Better. Webpage (last updated 31 July 2024).https://isyourlifebetter.net/cop-cities-usa/

PESP [Private Equity Stakeholder Project]. (2022), “Private equity firms now rank among the largest owners of US subsidized affordable housing properties” 2 Aug 2022. https://pestakeholder.org/news/private-equity-firms-now-rank-among-the-largest-owners-of-us-subsidized-affordable-housing-properties/

Williams, Eric. (1944 [1994]). Capitalism & Slavery. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

(MANUALLY) Replace this with bookmarks for pieces in sequential order