In part one, we explored Toni Morrison’s concept of rootedness in our struggle for Black/African liberation, particularly in the construction of grassroots economies and power. Here, I hope to advance our conversation by working to understand the neocolonial reality of Black/African peoples and communities in this country, so that – to paraphrase George Jackson – we do not fail to act in during these unusual times (Jackson 1972).

The internal (neo)colony: exploitation and capture

Black/African peoples and communities in the U.S. do not simply suffer from the deep inequalities of a racist system but constitute an ‘internal colony’ within this country. In Black Awakening in Capitalist America, written by Robert L. Allen during the urban revolts of the late 1960s, Allen describes how Black communities in the U.S. face a similar form of imperialist rule as foreign colonies and neocolonies, marked by “direct and over-all subordination of one people, nation, or country to another with state power in the hands of the dominant power” (Allen, 1969). Economist William Tabb (1970) agreed with this and outlined the conditions faced by Black people in urban ghettos as those of a colonized people: lack of labor freedom, suppressed wages, disposability and vulnerability of their labor, and dependency on external aid (welfare) and political power (patronage) at the price of comprising collective needs.

Allen accurately predicted that this state of internal domestic colonization was quickly shifting from that of a colony to one of a neocolony, where Black “leaders” would take the formal reins of power but still do the bidding of white elites and financial capital – a fact that both Allen (2005) and Tabb (1988) confirmed had occurred when they separately revisited this thesis years later. In 2024, we see that this colonial reality persists. Despite the Black faces that have inhabited the seats of many cities’ mayoral offices, C-Suites of multinational companies, and the Presidency and Vice Presidency, the masses of Black people continue to dwell in an internal colony. Nationally, as of 2022, Black unemployment [6.9%] is double white unemployment [3.4%], Black households earn $0.62 for every $1.00 white households earn, Black children are 2.7 times more likely to live in poverty v. white children, only ~2% of businesses are Black-owned (compared to 14% of the population), and even before the pandemic Black life expectancy was 3.8 years lower than for whites/Europeans – this gap has grown since the COVID-19 pandemic started (JEC 2022).

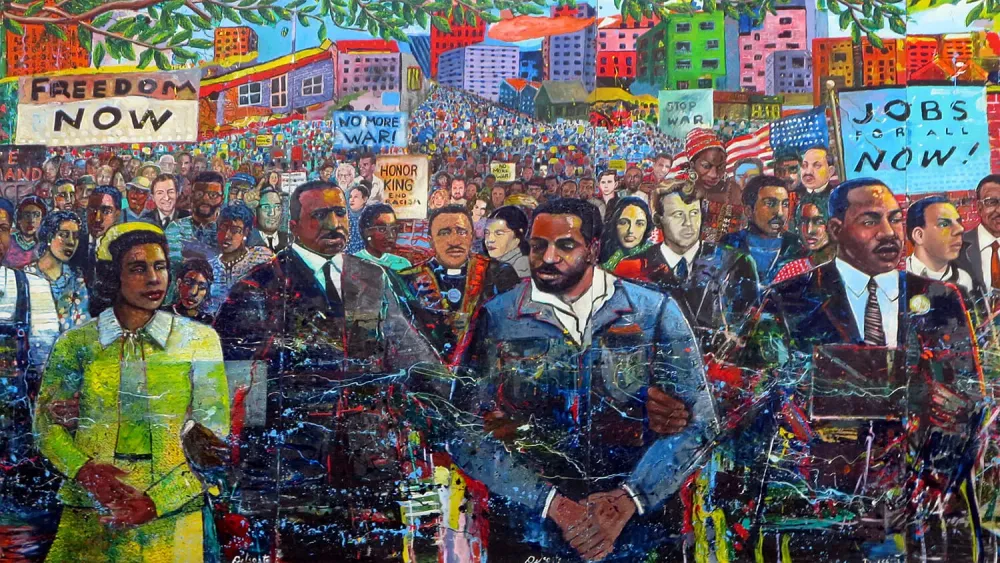

These are only examples, but each metric is worsening for most Black/African people in this country. This is to say nothing of Black/African working class and poor communities’ lack of political power, where they are pandered to but never partners in the supposed “democratic” process, or the occupation of Black/African communities by militarized police. Furthermore, instead of addressing the root causes of urban rebellions against deteriorating conditions, from the 1960s through today, state actors and their corporate allies have given Black/African communities resisting their colonization a choice: be co-opted through schemes of ‘black capitalism’ and nonprofit bureaucracy or face the full repression of the increasingly militarized police state.

Cooptation, representation, and corporate economic interests

Black capitalism, popularized as a policy by Richard Nixon (Baradaran, 2017), was always a false promise. As Allen says, in the U.S., “the social structure simply cannot accommodate those at the bottom of the economic ladder. Some individuals are allowed to climb out of deprivation, but [B]lack people as a whole face the prospect of continued enforced impoverishment. Increasing numbers will be forced out of the economy altogether.” Over the last 55 years, this has played out across the country.

Cooptation of rebellion through Community Development Corporations (CDCs) and nonprofit programs served as the alternative to ‘black capitalism.’ Though founded on radical ideals, by the mid-1970s, almost all CDCs were defanged of their radical potential and left in a state of constant resource scarcity and corporate dependence, resulting in a primary focus on promoting social services, providing small loans, and offering ‘technical assistance,’ all of which maintained the status quo (Tabb, 1988). In addition, many nonprofit organizations focusing on ‘urban issues,’ such as the Metropolitan Applied Research Center [MARC], enlisted Black leaders to implement corporate-backed efforts to contain revolt and resistance in cities domestically, across the globe internationally, and in prisons (Allen, 1969).

While black capitalism aims to integrate economic energies directly into the capitalist system, the capture of CDCs and nonprofits relies on incentives to push social change efforts into dead-end programs mired in bureaucracy. One could easily substitute the 1968-1970 period that Allen and Tabb analyze for 2020-21, and the general pattern holds: justified resistance pacified into patchwork nonprofit services, Democratic Party allegiance, and a docile population.

The same strategies are alive and well in planning and economic development programs that claim to be rooted in ‘social justice.’ Yet they always fall short because they do not address the root causes of injustices: primarily, that the capitalist profit motive of our capitalist system always positions Black/African people at the bottom rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. Charisse Burden-Stelly (2023) details this with the concept of Structural Location of Blackness, which illuminates Blackness as an economic relationship of exploitation, a disempowered political status, AND a structural placement at the bottom of the social order of the country. Though they talk about racial justice, planning and economic development institutions and their corporate backers cannot reckon with this Blackness, as that would mean reckoning with colonial domination, class warfare, denial of popular will, and the roots of economic injustices – which threaten their very being and legitimacy. Instead, representation has become a key component of planning and economic development processes at all levels, serving to cloud the reality of the protracted war on our people.

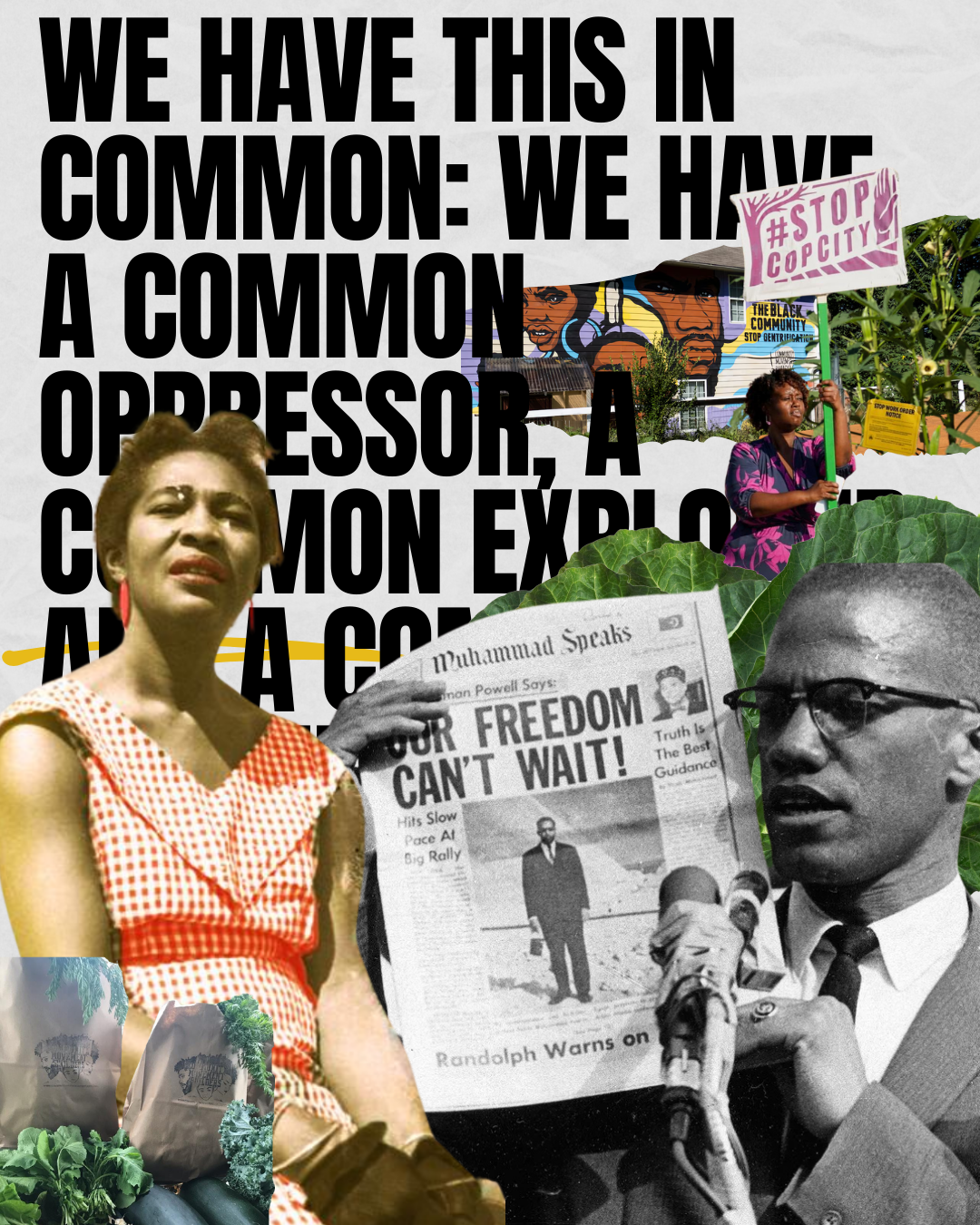

Within this war, scholar Orisanmi Burton (2023) warns that we cannot afford to confuse reform under a colonial situation with liberation from colonization, as the imperial state and its corporate allies utilize the complementary strategies of reform and repression to wage war against radicalism, collective self-determination, and popular sovereignty. In a time where we have just seen the failure of a presidential campaign run on representation and identity reductionism (Caines, 2024) and built the false promises of reform under neocolonialism, we must not forget that this system is intentional – that it is a strategy in the war against our popular self-determination and sovereignty.

Where do we go from here: colonial domination or collective struggle?

For centuries, Black/African peoples and communities have resisted under empire, from enslavement to colonization to neocolonial subterfuge. The revolts of the late 1960s and early 1970s, due to deteriorating conditions and the disillusionment with integrating into a ‘burning house,’ are part of this resistance. Yet then, like in 2020-21, a historic neocolonial counterinsurgency attacked Black/African liberation struggles and shaped our current reality. This has led to the dilution and demobilization of more radical, communal economic development efforts that were informed by Black Southern social relationships and land-based practices, as well as inheritances from traditional African societies. Channeling Toni Morrison, we can understand that during these counter-revolutions, as in post-Reconstruction and our kidnapping and enslavement, our roots were cut from us and the foundation of our ancestors tossed aside.

This is colonial violence, and we must combat it. We must go beyond surface critiques and understand planning and economic development’s role in maintaining neocolonialism and managing the war on our people and communities. Unless we divorce the tools for (re)constructing economies from the white supremacist patriarchal ideologies, colonial policy frameworks, and exploitative material flows of global empire, these practices will only perverse imperialist domination by another name. Or, as Joshua Briond recently put it, we must “abandon the burning house” of the U.S. empire (Briond, 2024).

Once we recognize this and decide to struggle against our (neo)colonial status, we can take up the work that Robert Allen laid out for us in 1969: “the continuing main task for the [B]lack radical is to construct an interlocked analysis, program, and strategy which offers [B]lack people a realistic hope of achieving liberation” (Allen, 1969). In the next and final piece of this series, we will look at what it might mean to construct interlocking solutions and prepare our counter-war against (neo)colonization.

References

Allen, Robert L. (1969). Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytical History. DoubleDay, New York.

Allen, Robert L. (2005). “Reassessing the Internal (Neo) Colonialism Theory” in Journal of Black Studies and Research, 35(1).

Baradaran, Marsha. (2017) “A Bad Check for Black America”. Boston Review. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/how-nixon-swindled-black-businesses/

Briond, Joshua. (2024) “The case for abandoning the burning house”. Mondoweiss. https://mondoweiss.net/2024/11/the-case-for-abandoning-the-burning-house/

Burden-Stelly, Charisse. (2023). Black Scare / Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States.University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Burton, Orisanmi. (2023) Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Caines, Erica. “The Democratic Facade: ‘Practicality’, Identity Reductionism, and the Erosion of Genuine Change.” Hood Communist. https://hoodcommunist.org/2024/09/05/democratic-facade/

Morrison, Toni. (1984). “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation”. In Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation. Ed. by Mari Evans. DoubleDay, New York.

The Joint Economic Committee (JEC). (2022). “The Economic Status of Black Americans, National and State Level Data.” https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/democrats/2022/2/the-economic-status-of-black-americans

Tabb, William. (1970). The Political Economy of the Black Ghetto. Norton & Company, New York.

Tabb, W. K. (1988). “What Happened to Black Economic Development?” The Review of Black Political Economy, 9(4).

Austin Cole was raised in Springfield, Ohio, and his people come from the Mississippi Delta and Birmingham, Alabama. He is a city planning practitioner focused on climate justice, transforming economic systems, and Black liberation. He is a member of the Black Alliance for Peace and co-coordinator of BAP’s Haiti/Americas Team.

(MANUALLY) Replace this with bookmarks for pieces in sequential order