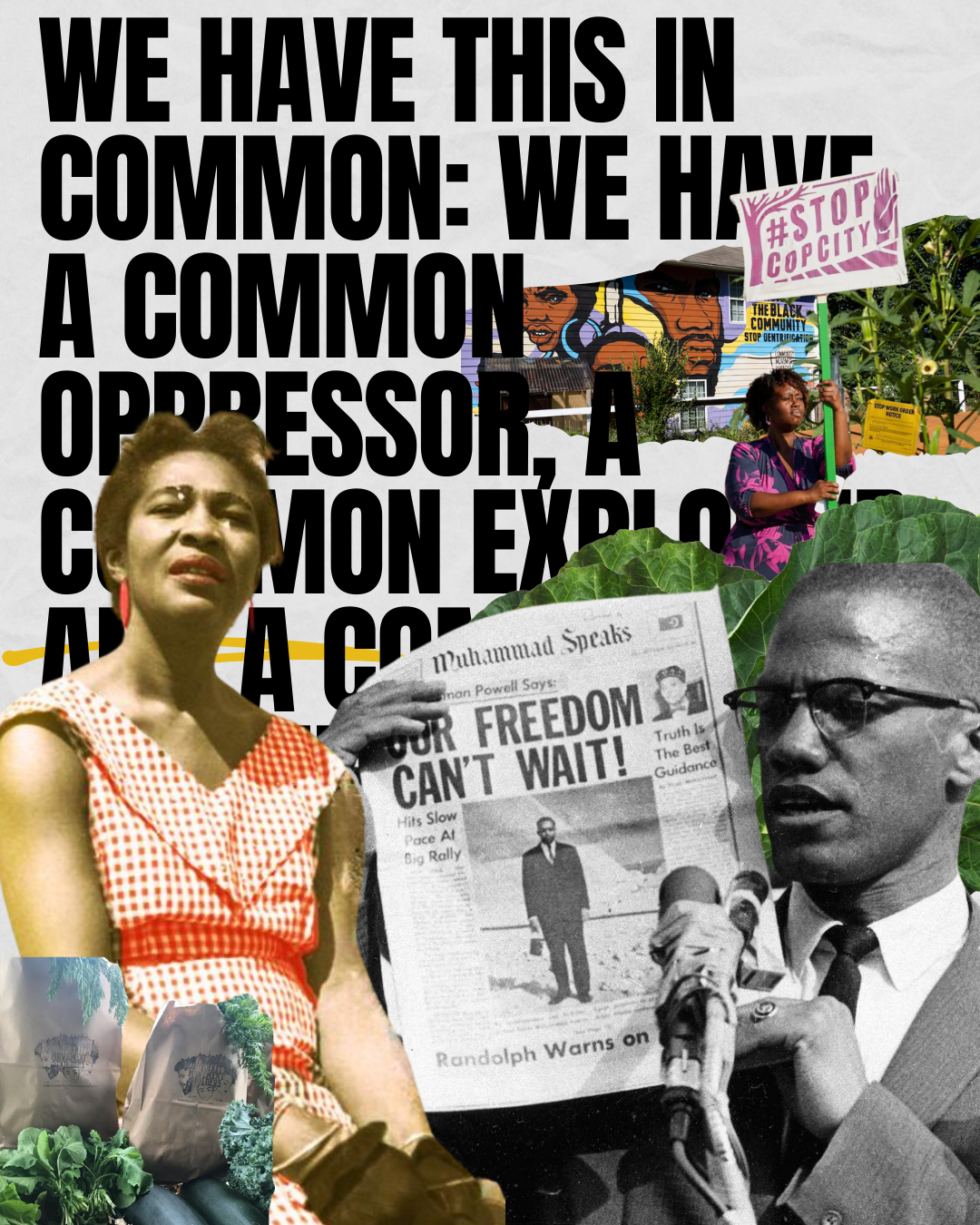

“You have to go back and reach out to your neighbors who don’t speak to you. And you have to reach out to your friends who think they are making it good. And get them to understand that they–as well as you and I–cannot be free in America or anywhere else where there is capitalism and imperialism. Until we can get people to recognize that they themselves have to make the struggle and have to make the fight for freedom every day in the year, every year until they win it.” – Ms. Ella Baker

In part II of this series, we traced the history and current context of the war on Black/African peoples in the United States, the current neocolonial conditions under which our peoples and communities exist, and the way that planning and economic development continue that status quo. Here we look at how we wage a counter-war by deploying strategies for constructing grassroots economies, breaking neocolonial dependency, and struggling everyday toward liberation.

If we understand the conditions of Black/African peoples in this country to be conditions of a war currently waged through neocolonial domination, then any pursuit of liberation, justice, or self-determination must work to unearth and conquer the roots of the violence and oppression inherent to this system. Here we borrow Orisanmi Burton’s notion of “counter-war” to guide our strategic direction. Burton (2023) pulls from the example of the freedom fighters of the Attica Prison Revolt in 1971 and describes a counter-war not as a method of violent retribution against the state, but as war against conditions of war, which aims to destroy the oppressive conditions imposed on the incarcerated rebels and build a future of self-determination and radical possibility.

We can see the construction of Black grassroots economies and planning as a form of counter-war against the local and regional neocolonial domination that defines our reality. Pulling from a tradition of bottom-up collective self-determination and liberation, the scholar and prison industrial complex abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2022) encourages the expansive idea of creating ‘abolition geographies’ through building forms of local ‘grassroots planning’. These forms of planning oppose domination and allow ordinary people to create spaces and places of freedom to take control and power of their collective destinies and resources. To do this, in the face of various social crises, Gilmore encourages us to not to ask the technocratic question of “what-is-the-solution?”, which limits imaginations and focuses on ‘wins’ that are too often co-opted into reforms that don’t shift the conditions of neocolonial domination. Instead, Gilmore asks us to aim towards a view of how we construct grassroots-driven alternatives by asking, “If not this, then what?”.

This open-ended question introduces possibilities for building collective self-determination on a local level and creating consciousness among ordinary people about our capacity to affect transformative change in our lives. Towards answering ‘if not this then what?’, here I offer six strategies that might orient priorities in constructing grassroots economies. These have become apparent to me through processes of community-engaged research, grassroots organizing, designing alternative economic initiatives, building community across geographies, and reflecting on past experiences navigating ‘social justice’ work under this capitalist system.

Strategies of counter-war

The first strategy that we look at is the building and advancement of political consciousness through organizing efforts and liberatory placemaking, which allows the people to be in the driver seat of the ever-changing circumstances around them. Liberation through political consciousness development and building a sovereign culture (requiring a real ‘rootedness’) are deeply intertwined. It is the process of action and struggle within an engagement in political-economic and cultural projects that creates a more revolutionary and solidaristic identity and material relationship among and between the people. On a practical level, this means that engagement with the grassroots organizing to meet people’s needs, agitational politics to fight harmful systems and structures, and mass consciousness-raising are fundamental inputs and ongoing practices of making a people, place, and culture. This could be work-study political education programming, participatory action research projects, mass assemblies, or other initiatives. In the case of BAP-Baltimore, the organization has committed to monthly ‘Town Halls’ that seek to educate and organize the masses of people to connect their everyday struggles to topics like militarization, the political duopoly’s exploitation of the working class, and people(s)-centered human rights (BAP-Baltimore, 2024).

Second and related, is fostering mass-based community power toward control over our lives. Building with popular movements and supporting processes of mass-based power are critical to this project and help to avoid the neocolonial tactic of ‘elite capture’, which occurs “when the advantaged few steer resources and institutions that could serve the many toward their own narrower interests and aims” (Taiwo 2022). This is fueled by the identity reductionism and neoliberal representation politics that we discussed in part II (Caines, 2024; Springer, 2024). Elite capture is endemic to planning and economic development practice and helps derail radical and revolutionary organizing. Avoiding such capture requires organizing mass-based community power rooted in shared principles, institutions, actions, and objectives that can help win new terrains of community control and defend what has already been achieved. As Erica Caines said in describing organizing that she is a part of in Baltimore, “it is a struggle in how people understand ourselves as colonized people because of the conditions they are finding themselves within…. An emphasis on community control is an emphasis on the same types of self-determination as in an anti-colonial struggle: we are worthy of control over our lives.”

Building this control through mass-based community power might look like a greater emphasis on local ‘Build and Fight’ campaigns in the example of Cooperation Jackson and other efforts that combine cooperative economic models, community-based production and workforce training initiatives, mass-based people’s assemblies, and other methods (Akuno & Meyer, 2023). What this cannot be is a strategy that is dependent solely or even primarily on electoral campaigns that are easily coopted or subsumed to serve elite interests, but instead must focus on building the capacities for people and popular institutions to exercise collective self-determination.

Third is the strategic use of ‘the state’, especially municipal resources and power, to demand that assets and resources for survival be redirected to the grassroots. This must be done in ways that do not undermine the dignity of the people and their communities. We know that the state, including our local governments, is not singular or static. It is partially formed by the modern world economy, and thus owes its legitimacy to a much broader economic and political system (Wallerstein, 1974; Gramsci, 1935). Nonetheless, state actors, offices, and resources can act both in support of and in opposition to the domination of the capitalist-imperialist world system. As Sabrina, a member of the grassroots collective Anti-Displacement NYC put it, “there is such a value to organizing on the local level and having municipal knowledge of how you run a city and take that to organizing. We need to understand what we’re doing, so that when we do seize power, we are equipped to do so, and know how to distribute water, how to utilize financial systems to yield outcomes that we want.”

Nonetheless, when engaging with the state, we must start with the organized power of the people and focus on restructuring relationships. One framework that can anchor this process is People(s)-Centered Human Rights (PCHRs), coined by Ajamu Baraka and utilized by the Black Alliance for Peace [an organization that I am a part of]. This understanding of human rights asserts that they “emanate from and address the everyday realities, needs, and challenges of racialized and colonized people;” are guaranteed only through bottom-up mass struggle; and are rooted in Black/African revolutionary traditions (Baraka, 2018). According to Baraka (2018), this requires four steps, “1) an epistemological break with a human rights orthodoxy grounded in Euro-centric liberalism; 2) a reconceptualization of human rights from the standpoint of oppressed groups; 3) a restructuring of prevailing social relationships that perpetuate oppression; and 4) the acquiring of power on the part of the oppressed to bring about that restructuring.”

It is from this place of power that engagement with state and municipal processes might help enable collective self-determination, not stifle it. Doing so might allow us to win more from the state by stepping into our collective power, and as my comrade Nick has said, by “building a culture of demanding more” (Richard-Thompson 2024).

Somewhat in opposition to state engagement is our fourth strategy, carving out liberated zones and/or communal space-taking, which can support spaces of renegotiating social relationships to embody the imagination and materiality of what liberation might be. Liberated zones and communally-seized spaces are tools of fighting against economic oppression and creating grassroots-based alternative economic arrangements. In the specific case of Buenaventura, the port city on Colombia’s Pacific coast, a 2017 civic strike led primarily by AfroColombian groups shut down the most important port in Colombia for 22 days and forced the government and private actors to negotiate with the ‘Buenaventura Civic Strike Committee for Life with Dignity and Peace in the Territory’ to create new economic arrangements around the port. While this was a critical strategic and motivational victory, the strike’s appeals to inclusion within Colombia’s capitalist and hierarchical system have limited the potential to create transformative grassroots economic shifts.

Though highly dependent on local context and political-social-economic conditions, this strategy might provide a possible framework for grassroots economic planning and practice beyond capitalism and represent a tool for winning concessions from the state and private actors. However, it must involve wider system transformations, or else it is vulnerable to cooptation, retribution, and sabotage.

That brings us to the fifth strategy, the strengthening of community self-defense. While this would almost certainly imply self-defense in the armed tradition of the Black Panther Party, Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and Deacons for Defense and Justice, self-defense also includes protecting peoples’ ability to survive, live healthy lives, and stay in their homes and neighborhoods. This means protecting individual households from predatory actors like aggressive corporate landlords or private equity companies seeking to buy their homes via methods of sabotage like tax lien purchasing; creating more collectively self-reliant, healthy, and resilient food and energy systems; and many others tactics. Simply put, we cannot struggle for liberation and self-determination if we cannot survive as communities and individuals. Organizations like the Community Economic Defense Project in Colorado, the National Black Food & Justice Alliance, and the People’s Network for Land and Liberation are doing critical work here. This also means building refuges or safety nets for people and communities who may need to leave home, which many autonomous collectives are coordinating.

Sixth and finally, in defending and resourcing our communities, we come to the strategy of establishing authentic mutual relationships of international solidarity and intercommunal cooperation that are not premised imperialist, patriarchal structures. We understand that the same primary contradiction that oppresses the people of Cuba or Haiti or Palestine or Sudan – white supremacist, patriarchal imperialism – also leads to oppression, exploitation, and state violence against Black/African peoples in the U.S. Robert L. Allen (1969) argued that Black radical transformation in the U.S. would require both an economic program on a national level and the proliferation of international solidarity with ‘Third World’ peoples to defeat imperialism through an “all-encompassing, planned communal social system on a national scale and with strong international ties,” which would “begin to break down capitalist property relations within the black community, replacing them with more socially useful communal relationships.” In this way, through solidarity and cooperation, we will strengthen ourselves and all African and colonized peoples globally.

Humanity and liberation through strategic counter-war

At minimum, these strategies can be seen as forms of survival and ‘counter-war’ against the war of imperialist domination visited upon the racialized, colonized, and oppressed peoples of the world, including and especially Black/African peoples in the United States. More broadly, they might also contribute to a re-negotiation of human dignity and self-determination against the oppressive norms of the white supremacist capitalist-imperialist-patriarchal status quo, which reduces humanity to a measure of our usefulness to the ongoing systems of hierarchical production and that is the foundation of traditional forms of local planning and economic development. In this way, such strategies can be tools to create a ‘counter-humanism’ (Burton, 2023) that emerges from the masses of people, neighborhoods, and communities themselves, and enables our collective liberation.

In the final piece in this series, we will re-ground ourselves for this counter-war and see how struggling through the concept of ‘The Black Commune’ might help us remain steadfast on the path toward liberation.

Note: I extend my deepest appreciation to the organizers and workers involved with the following projects, who were gracious in the time and space they afforded me as researched and explored the concepts that appears here: in Cuba: La Red Barrial Afrodescendiente, Afrodiverso, Mas que Ile Mas que Omo Mas que Oko, La Muñeca Negra NaturArte, Sorpresas de Ocha, Taller Yoruba, Todo Turbante; and in the U.S.: Anti-Displacement NYC, Aurora Participatory Democracy Hub (Illinois), Black Alliance for Peace – Baltimore, Black Alliance for Peace – Chicago, Boston Ujima Project, Central Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation, East New York Restoration, Liberation Through Reading (Maryland), , Ujima People’s Progress Party (Maryland).

References

Akuno, Kali & Matt Meyer (2023). Jackson Rising Redux: Lessons on Building the Future in the Present. PM Press: New York.

Allen, Robert L. (1969). Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytical History. DoubleDay, New York.

BAP-Baltimore. (2024) “Why Town Halls.” Instagram. www.instagram.com/p/C8KyMOwyIcm/

Burton, Orisanmi. (2023). Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Caines, Erica. (2024). “The Democratic Facade: ‘Practicality’, Identity Reductionism, and the Erosion of Genuine Change.” Hood Communist. 5 Sep 2024. https://hoodcommunist.org/2024/09/05/democratic-facade/

Gramsci, Antonio (1935 [1989]). “The Intellectuals” In An Anthology of Western Marxism, Ed. By Roger S. Gottlieb. Oxford University Press: New York.

Gilmore, RWG. (2022). “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning.” In Abolition Geography, Verso, New York, 316-344

Richard-Thompson, Nick. (2024). “Demanding More in the Struggle for Collective Liberation – A Conversation with Nicholas Richard Thompson, Part II.” Black Agenda Report. 30 Oct 2024. https://www.blackagendareport.com/demanding-more-struggle-collective-liberation-conversation-nicholas-richard-thompson-part-ii

Springer, D. Musa. (2024) “Neo-Colonial Capture, Culture, and Neo-Liberalism.” Hood Communist. 8 Nov 2024. https://hoodcommunist.org/2024/11/08/neo-colonial-capture-culture-and-neo-liberalism/

Taiwo, O. (2022). Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everything Else). Haymarket Books, Chicago.

Wallerstein, I. (1974 [2011]). The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press, Berkeley.

(MANUALLY) Replace this with bookmarks for pieces in sequential order