It isn’t a revelation that some African people born in the United States have an irrationally strong attachment to the idea of America. That idea is all tied up in the myth of a virtuous American identity, borne of overcoming adversity through ingenuity and perseverance. Whether from self-preservation, self-hate, or delusions of grandeur, it isn’t uncommon for oppressed and marginalized people to attempt redemption by washing their history of its subversion and exchanging it for a narrative that soothes the ego.

The effort to merge African identity with colonizing Western powers is as old as the French and British flags flying over African and Caribbean nations. It’s as old as white people on the East Caribbean dollar. It’s as old as the imposing European syllables and sounds fumbling around African mouths across the diaspora. It sticks out as awkwardly as a round peg in a square hole. Yet, it surrounds the African in daily life. It implores them to forget themselves, to shed old garments and take up the disguises, words, arms, and the goals of imperial powers. It convinces us that these violent imperialist nations were built by us, rather than stolen through bloodshed, starvation, and disease.

It makes us participants.

Rappers draped in the American flag. (Left to right, Sexyy Red, Juelz Santana, Da Brat.) Sources: Essence and Billboard.

The desire to take credit for establishing America reveals an underlying allegiance to the project of America as a whole. It relies on the assumption that America, whatever its origins, is a net positive, something to take pride in. It also obscures the violence inherent in the formation of a nation by retroactively giving consent for the nation in question to exist, consent that neither the stolen Africans nor the indigenous populations of Turtle Island gave. America was not built; it was stolen.

Land was wrestled from indigenous tribes and parceled out to European men who stole African people to work it, learn it, and cultivate it for profit. Infrastructure was built for the use of European landowners, who instilled in themselves the authority to lord over the life and death of those deemed lesser. With that ill-gained authority, they forced African people to pave roads and build homes and commercial centers under threat of whip, mutilation, and further physical punishments. Legislative buildings were built by those stolen people, in which those Europeans signed African dispossession into law. They cleared away entire tribes, histories, vegetation, and animals to assemble their violent country on top of the ruins.

Why would we take credit for something that shouldn’t even be here?

Our forced participation in this cursed place through tax dollars spent on genocidal wars is enough. We were already made nonconsenting conspirators to their crimes, sent to fight their wars against their other colonial and imperial victims. We don’t need to consent to further identification. We don’t need to take credit for this place.

This is not to say that African people have not made anything valuable on this soil. Displaced Africans created thriving communities, learned the land, established loving bonds, and produced art reflective of their historical and cultural position. Art that, like the bodies, labor, homes, and everything else African people here have managed to establish, is often taken, imitated, watered down, and neutralized in service of the creation of a fictional “American” culture.

Unfortunately, the effort to retain some sense of ownership over those cultural products has led some Africans to demand credit for America itself. Some Africans, desperate for recognition of their contributions and resentful that their cultural inheritance has been attributed to generational thieves, have tried to find shelter within the umbrella of America, to lay claim not only to the stolen art and history but to the country itself.

This strong resurgence of pride in a “Black American” identity, which accompanies a stubborn assertion that we have as much “right” to Americanness as white patriots do, is a gross misdirection. There were plenty of issues with the term African American, a term that became fashionable in respectable circles and regained popularity in the 1980s, but for all of its flaws it should not be lost on us that the current mainstream preference for “Black American” removes Africa completely yet retains, and even emphasizes, American.

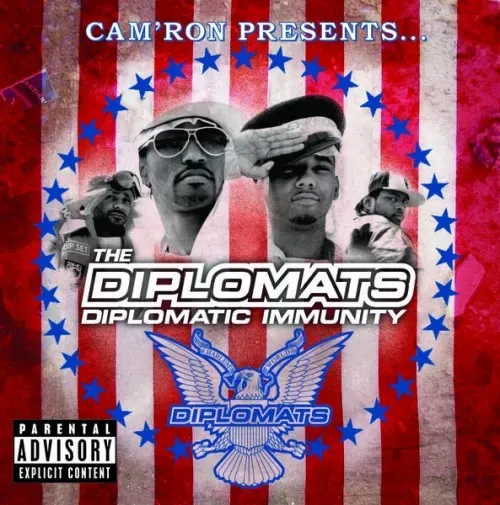

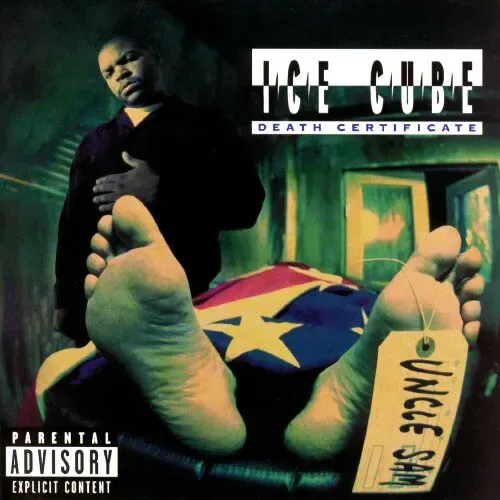

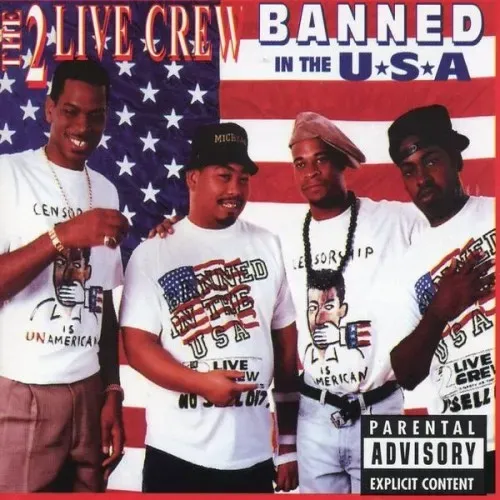

Album covers curated by Dave Bry in his Medium article "The American Flag On Rap Album Covers Throughout History." Source: The Awl

The preoccupation with owning Americanness can be seen in circular and divisive social media discourse about British or Caribbean Africans playing “Black American” characters in films, whether fictional like Celie in The Color Purple, or biographic like Harriet Tubman and Fred Hampton. This particular manifestation of back-door patriotism is fueled by anti-immigrant, anti-African rhetoric from groups like the Foundational Black Americans (FBA), and it is indicative of a larger cultural regression incited by patriotic reactionaries who intend to erase all traces of Africa in order to sterilize our people into complacent American individualism.

This back-door patriotism is tempting for a people who have been told constantly that outside of the arbitrary borders of America, they have no culture, no language, and no identity, so they must hold tight to what was made here and protect it as if it is all that we have ever had. But this backward allegiance must be resisted forcefully.

The borders of the United States are violently maintained–and not only via walls, forced deportations, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement kidnapping squads. They are maintained and legitimized within the cultural output of Americana aesthetics, by billionaire Black celebrities wearing the stars and stripes, by the romanticization of America as a metaphor (an overused and boring metaphor), its symbolism, and iconography. Like clockwork, a pop singer or rapper will wrap themselves in the flag like armor, and their fans take up arms for them against criticism. They will dig their heels in and bemoan that we should be able to “reclaim” the imagery. They will argue that draping yourself in the flag isn’t necessarily patriotism because those artists occasionally make shallow critiques of select presidents or legislative policies. The same artists and pop celebrities that have nothing to say about the slaughter in the Congo, the imperial assaults on Haiti, the genocide in Palestine, the expansion of cop cities, and the attacks on the Black poor and working class here in the so-called United States.

Artists like Beyonce, whose political efforts extend no farther than a Democratic Candidate’s campaign rally, are also, allegedly, subtly critiquing the United States via American flag iconography? What exactly is the critique? And what critique (if we assume it exists) can be taken seriously if it cannot be distinguished from a tacit endorsement? We are expected to accept that in the same place where Nina Simone, Gil Scott Heron, and Tracy Chapman spoke and sang clearly and unequivocally, we now have to produce a magnifying glass to find an alleged critique hidden under layers of allegedly subversive Americana imagery? If you have to search that hard for the critique, then it is likely nothing but a figment of your intense desire for it, brought on by the desperation to find something about this country worth saving and protecting. What is evident in the verbal gymnastics it takes to claim the glory of a country while denying your participation in its gore is that these protectors of American iconography see no issue with the illegitimate country itself, just with their exclusion from it.

There is nothing to reclaim here; that symbolic soil is desolate. The American flag is cursed fabric stained with blood. The stars and stripes are symbols of global Western violence and calculated destabilization. This is the flag that stands for the assassinations of democratically elected leaders, CIA coups, and funded militias. The American flag is stamped on the sides of bombs that drop on colonized people yearly, monthly, and daily.

In the words of Malcolm X,

Don’t think you don’t look Congolese. You look as much Congolese as a Congolese does. They got all kinds of Congolese over there. How would you feel if one of them walked up to you and asked you about what your government is doing in the Congo?

Even symbolically or metaphorically, why should we, as stolen and colonized African people, identify with the thieves and murderers?

Why should we align ourselves with the colonizers and not the colonized?

So, at this point, the question that usually comes up is “Well, what do you want Black Americans to do?” Although it is typically asked in bad faith, I will still answer it. Drop the “American” because you are not. Find in yourself the history and legacy of people who resisted colonization and expand the breadth of the cultural inheritance you possess outside of these imaginary borders. Aim for bigger and better things than Black faces at the helm of bloody empires and pop stars dressed in the stars and stripes. Stop defending a flag that will never defend you. Unite with other colonized people around the globe who are fighting against Western hegemony and imperialist domination. There is no need to go down with this ship.

The unification of colonized people worldwide is an assertion of our humanity against the dehumanization embedded in American patriotism. It is the political clarity that comes with understanding ourselves as Africans that opens us up to deeper political, cultural, and revolutionary legacies. It is strengthening our tie to the continent and asserting not only solidarity but a shared future built on a shared past.

Rejection of Americanism is necessary for our survival. We do not need to take credit for building this place. We need to unite with the colonized of the world who are fighting to tear it down, reclaim their dignity, and destroy the forces of Western colonial violence that enchained and dragged us here in the first place.