As a child growing up in a South Jersey suburb, the playground was my sanctuary. From ages two to seven, I lived in a duplex where the neighborhood jungle gym and basketball courts were visible from my bedroom window. Some of my fondest memories occurred near swing sets and sliding boards. I can still remember pumping my six-year-old legs to soar as high as I could into the sapphire summer sky. Though the steel and concrete playground of the 1980s produced more than enough bumps and bruises, it was my safe space for dreaming. It was where we played freeze tag and listened to music. It was where we ate our gummi worms and played hide and seek. For me, playgrounds represent laughter and freedom. The playground was where I felt most liberated.

Forty years later in Baltimore, MD, my husband and I are raising an eight-year-old and a toddler who enjoy the wonder and magic of playgrounds, just as I did. Twenty-first-century play structures are shinier, more colorful, and more inviting than they were in my day. Sensory placards state instructions for ASL, crumb rubber has replaced jagged rocks and gravel underfoot, notes from built-in xylophones pepper the air, and even the merry-go-rounds come with a warning label. These new and improved parks consider safety, inclusiveness, and optimum play…if you’re in the right neighborhood.

When Baltimore poets embraced me 25 years ago, I knew I wanted to live here. The city is vibrant and alive. It has a rich culture of art and activism. In 2016, my husband and I became fully invested when we purchased our first home in Ashburton, a beautiful neighborhood in northwest Baltimore. To this day, we have few complaints. In fact, a state-of-the-art playground is being built two blocks from our home. However, like most US cities, Baltimore is highly segregated and disinvestment reigns supreme, particularly in West Baltimore. Though our neighborhood is a gem, it couldn’t be more different from Harlem Park, where my son’s homeschool collective meets weekly during the school year.

The playground at Harlem Park in Baltimore, MD. | Credit: B. Sharise Moore

While our neighborhood boasts clean alleyways, towering trees, single-family homes, and manicured lawns, Harlem Park is comprised of countless vacant row homes, deteriorating buildings, and overflowing trash cans. The same can be said of the playground, two blocks from the homeschooling collective site. Baltimore’s urban blight and crumbling infrastructure led me to write my forthcoming picture book, A City Dream. It also drove me to spearhead a playground renewal project for my son’s homeschooling collective.

Jamii Leadership Homeschooling Collective, founded by Latania Chisolm, has been serving Baltimore families since 2018. Scholars who attend Jamii enjoy weekly horseback riding lessons sponsored by the Shuster Foundation, gardening with Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm, theatrical presentations, field trips to regional museums and local orchards, and more alongside their academics. Jamii is a wonderful organization, and its students—as well as the youth in Harlem Park—should be able to play in a safe, functional, clean, well-kept playground with swings and a functional sliding board.

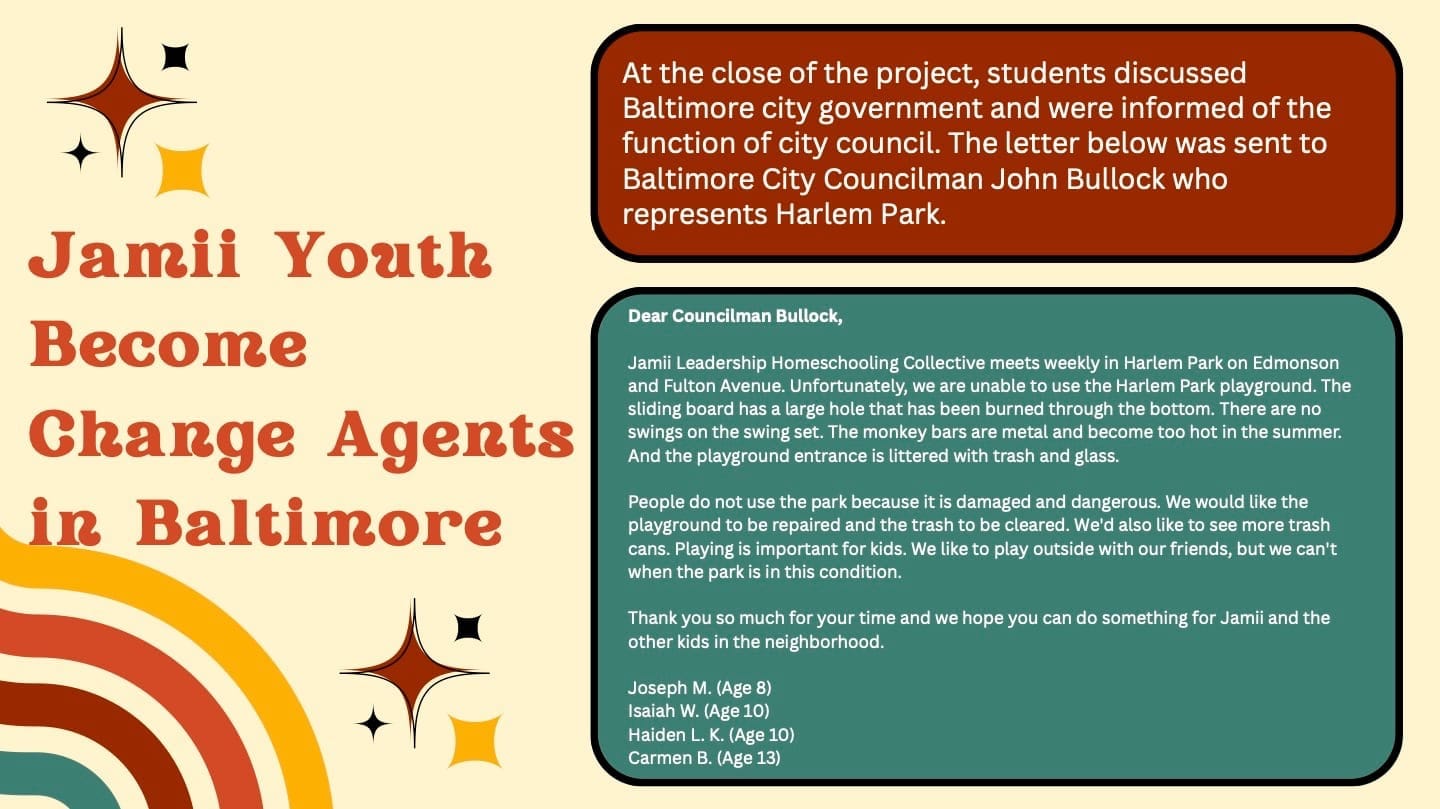

After hearing the student’s complaints, we got to work. The students formed their own definitions of community. They discussed the improvements they’d like to see in their own neighborhoods. They shared their feelings about Harlem Park and the city as a whole. Then, they learned about the history of playgrounds and the future of play parks, drew pictures of their ideal playgrounds, and created dioramas. Once this was complete, the students discussed city government and the duties of the mayor and city council. Identifying Councilman John Bullock as the city councilman in charge of Harlem Park, the students wrote him a letter voicing their displeasure. In his reply, he thanked the students and vowed to make improvements.

When doing the work, don't forget the kids

Part of liberation work is defining freedom and what it looks like. It’s asking ourselves when we’ve felt most free—at the top of the swing or the bottom of the slide—and how we can return to those moments. Liberation work is dreaming. It’s creative problem-solving. It’s guiding our youth. We must model for them what justice and accountability look like. Those involved in liberation movements are quite aware that this work does not begin or end at the ballot box. However, sowing the seeds of leadership and community in our young people is essential. As we engage in this work, let’s bring our youth along. Let’s be sure to include them in our plans for a free and equitable future.